1,000 Drones v. Our DDG

how do you fight a chimera of Geordi, Data, and Spock?

A constant in warfare is change. War is the ultimate human manifestation of Darwinism, evolving as technology and theories of warfare advance to enhance a nation's ability to project its will militarily.

Deadliness, range, impact, and scale. Nations are always looking in these areas to advance, and as such, get an overmatch capability that an enemy cannot counter.

The compound bow, the horse, bronze-then-iron-then-steel-then-composites, gunpowder, the external-then-internal combustion engine, coal-then-oil-then-nuclear, submarines, aircraft, chemical warfare, nuclear weapons, and so on and so on.

Nothing is static, but you have to be careful. The post Cold War assumptions about the primacy of nuclear weapons over conventional power almost led to disaster in the Korean War. Forgetting that, all our services fell in love with a TomorrowLand mentality about Future War™ that led to a sub-optimal performance in the Vietnam War.

The assumptions of the primacy of the Cold War AirLand Battle Doctrine success and false lessons from the extended exercise known as Desert Storm festered for a decade that led to suboptimal performance in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In January 2025, we do have clear indications that we are on the cusp of another phase of military evolution that may…may…be on par with the maturity of aviation and submarines a bit more than a century ago, and steam power and armored ships a half century before then.

We have an intersection of rapidly developing technology and computer code where the evolutionary is bleeding over to becoming revolutionary.

We are getting hints of this in the development of drones in Russo-Ukraine War that re-ignited in 2022.

We are familiar with the decades-old term “Smart Weapons” - but in today’s context, those are actually rather dumb.

The rising power of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the amazing amount of storage capacity and speed of modern computing—perfect for miniaturization—is coming into maturity at the same time as amazingly affordable optics and sensors.

Much of this is not bleeding edge, it is already here. It is just in the building stage.

Here is the inflection/intersection point that need to finish up their maturity in order to tip into revolutionary:

Autonomous AI driven multi-spectrum seeker-heads

Broad-access, high-fidelity, multi-spectrum geospatial information

Extended range platforms that range the spectrum of cheap/many/slow to expensive/fewer/fast

Volume production that drives down cost

Distributive additive manufacturing

The appropriate ROE to enable full use of the resulting weapons system

National will

If you don’t get the full impact of this, few people have explained it as clear as Marc Andreessen in his interview with Peter Robinson at The Hoover Institute. I’ll put the full video below, but I think reading the transcript starting at the 55:25 mark is good.

PETER ROBINSON: I asked someone I probably shouldn't name because he doesn't. I don't know whether this was in confidence. I asked a former admiral the other day, if shooting begins over Taiwan, how close can American aircraft carriers get? And he said, American aircraft carriers must stay 1,000 miles away from any hostile activity. The Chinese have already pushed the surface perimeter out 1,000 miles. Anyway, to your point:

MARC ANDREESSEN: Hypersonics are coming and then drones are coming.

PETER ROBINSON: Exactly.

MARC ANDREESSEN: "We're at the very beginning of drone warfare. The drones are going to get very sophisticated and they're going to be manufactured in much higher quantities. Every time you see a drone today, just think of that being 1000 drones. What could a naval destroyer even do against 1000 incoming drones armed with bombs big enough to blow a hole in the side of it?"

OK, then what? If you assume that Andreessen is more right than he is wrong, which I do, then what do you do?

First, this is the worst-case, high order scenario against your worst-case, high-order threat. Not unlike planning for nuclear war with the Soviet Union in the Cold War, you have to plan for it, prepare for the fight, and be ready to win…but you cannot design your entire military around that one threat. You have to be flexible enough in mindset and equipment to meet the full spectrum of national security requirements in gradations up to that.

However, should the big fight come, how do you win? How do you project national will? How do you “get there?”

Like the machine gun, land mine, and massed artillery, AI empowered long range attack drone can create a “no man’s land”, but that is OK. Machine guns, land mines, and massed artillery did not make everything else obsolete. It did not end war. Smart nations evolve.

Same in the maritime domain where we’ve been confronted with mines, submarines, aircraft, nuclear weapons, and regiment sized fleets of Backfire bombers armed with supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles.

We’ve been here before. We did not leave the field. We did not surrender the battlespace without a shot.

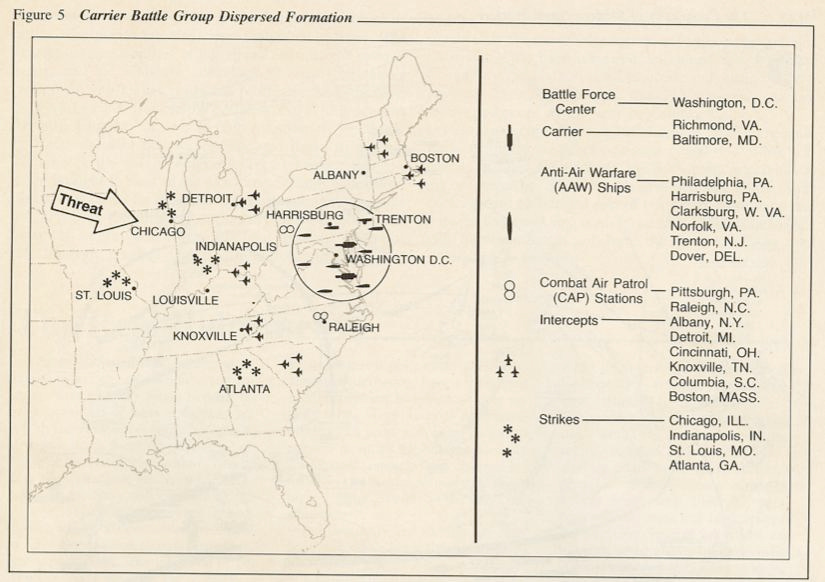

This is a graphic from my copy of the 1986 Maritime Strategy.

The distance from DC to Atlanta is 475 nautical miles. From DC to St. Louis, 620nm.

1986 was 38 years ago. That is the same length of time from Orville Wright’s first flight, to Imperial Japan’s Kidō Butai decimating the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

We’ve been here before. The USA is the most inventive people on the planet. If we unleash that national superpower skill, we’ve got this challenge.

There will be counters to this new capability, there always are counters. You just need to develop them in time. One use of autonomy will drive the use of others.

Additionally, as my colleague Jerry Hendrix and I have emphasized for the past quarter-century, restoring range to our carrier air wings is critical.

Chicago is the threat?

Things don't change much

My thoughts:

1. Capability isn't cheap. The "FPV quadcopter with a grenade" may be useful in Ukraine, but it has neither the range nor the payload for a sea fight. Once you get to the longer-ranged systems, and heavier payloads, costs go up dramatically. MQ-9 Reapers are costing $30 million...and they are the LOW end. Filling the sky with cheap unmanned systems is plausible only for the close-to-shore fight. Any "loyal wingman" platform with useful performance will come with a tactical jet price tag.

2. Software is HARD. Processor speed is no longer the driving factor in capability, it's getting software that is reliable. And one issue with that has been that the software industry is not accustomed to working with classified capabilities, nor with the reliability demanded of military systems. They think in terms of commercial software that can be releases to let the early adopters do the final beta testing, then patched. Which won't work in combat.

3. Concur 100% on the need for range. The current air wing was designed for the needs of the 1990-2020 world. It's utterly unsuited to the needs of 2025 and beyond.

4. It's probably time to start experimenting with short-range defensive UAV capabilities. Both as active defense systems and as a way to deploy countermeasures.