This D-day anniversary I want to bring out a FbF I've run a few times over the years as it points out one of the hidden parts of the campaign that I want new readers to have a chance to read about.

Most attention, rightfully, is paid to the beach and the move inland, but to enable that success, a lot of work was done at sea to keep the beach and seas open ...

As the D-Day invasion was ongoing, the German Navy sortied what they could to try to drive the allies back across the channel.

The most feared were the U-boats based in France.

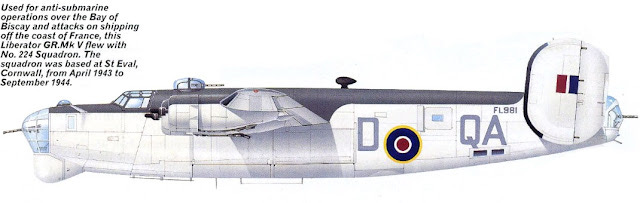

Please read the whole thing, but here is a nice summary of one of the under-told stories of WWII, Coastal Command.

On night. One crew. Two U-boats.

Fullbore.

“G-George” droned on through the night. Men drank coffee from thermos flasks, kept the chatter to a minimum, scanned the endless sea and began to feel the numbing weariness set in that came with these long over-water patrols. But adrenalin shot through their bloodstreams like amphetamine just after 2 a.m. when Foster announced on the intercom that he had a solid return on his radar 12 miles dead ahead in the vicinity of Ushant Island (Ouessant). It was too early to tell whether it was a French fishing smack or the conning tower of a U-boat. Moore corrected his course slightly to port to put the target in the path of the moon reflecting on the water. Three miles out the conning tower of a submarine was made out in the moonlight.

Coastal Command anti-submarine crews were trained to attack the moment a U-boat was detected and without deliberation. An undamaged Type VIIC U-boat, with a well-trained crew could crash dive beneath the surface in 30 seconds. Time was of the essence, as was complete surprise.

Immediately, Moore instructed Foster to switch off the radar in case the submarine had detection equipment, and then began to drop lower and lower, adjusting his course to keep the enemy up-moon until he was at 50 feet above the calm surface. McDowall, the navigator, took his position at the bomb sight. Moore ordered the four big bomb doors opened and as they slid upwards and outboard on their rollers, he could hear the hydraulic pumps working and sense the difference in the airflow note down the sides of his warhorse. Approaching the U-boat, which they calculated was making 10–12 knots in a westerly direction, they selected 6 depth charges from their quiver, attacking due south and 90 degrees to the path of the U-boat on her starboard side. Moore chose to leave the powerful 22 million-candela Leigh Light off to further keep their whereabouts secret. As they screamed in for the attack, the spare navigator, Pilot Officer Alec Gibb, DFC sprayed the conning tower with heavy machine gun fire (some 150 rounds according to the after action report) from his position in the nose. Moore and Gibb later stated they could see as many as 8 submariners scrambling from the tower to get to the deck guns. There was some anti-aircraft return fire, but it was too little and too late. They had caught them completely by surprise.

As they roared over the submarine at 190 mph, six depth charges, set 55 feet apart, were falling from “G-George’s” bomb bay, having been released by McDowall whose accuracy this night would be perfect. Three fell on either side of the submarine in a textbook straddling attack just ahead of the conning tower. A flame-float, designed to ignite when it hit the water was also dropped to identify the position of the submarine at the moment of attack. The rear gunner Flight Sergeant I. Webb watched in fascination as the detonations exploded white in the moonlight and appeared to lift the 700-ton submarine out of the water.

By the time they had climbed, swung around and were homing on the beacon of the flame float at the position of the attack, there was nothing left of the U-boat save for some floating wreckage and the oily slick of diesel fuel. A Type VIIC U-boat had disappeared and ceased to exist in a matter of seconds, the depth charges having done their job breaching the pressure hull and sending one of Karl Dönitz’ hunters to the bottom with all hands. One can only imagine the last minutes of terror for the more than 50 men aboard.

Sadly, when this submarine sank, there was no one who could identify which U-boat it was. Postwar accounting pointed to U-629, commanded by Oberleutnant zur See Hans–Helmut Bugs on its 11th war patrol. She had just slipped out of her pen at Brest the day before. Still, other researchers disclaim the U-629 identification, pointing instead to U-441, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Klaus Hartmann on its ninth and final war patrol. It is not my goal to be definitive as to the identity of the fifty or so men killed that night, that best being left to experts in the field. Knowing would bring the story to a satisfying close, but it will not lessen the tragedy or the courage of the U-boat men who died that night.

Moore settled his crew down after the last pass over the wreckage, and ordered a course correction to take them back on their patrol. At 0231, just twenty minutes after the first radar contact was made, “G-George” sent a message to command that they had sunk a U-boat. The men were charged with electricity, but they had a job to do and hours before they could return home to St Eval.Just a few minutes later at 0240 hrs, as they settled down at 700 feet ASL, Foster reported another radar contact 10 degrees off the starboard nose, this time just 6 miles ahead. Moore, with information from Foster, began to home in on the target, and at 2.5 miles range and 75 degrees to starboard, they sighted the conning tower of another U-boat on a northwesterly course running at an estimated eight knots on the surface. This time Moore needed to circle to port and come in on a course that would allow them to attack up the moon path.

Bringing the big Liberator down to 50 feet once again, Moore approached the U-boat at 110 degrees to its starboard side with plenty of time to set up another perfect attack at 190 mph. The remaining six Torpex depth charges were released at 55-foot intervals as well as a flame float. Again, Gibb, the spare navigator in the nose, was firing his machine gun at the conning tower, which answered this time with flak and tracer fire. As they roared overhead, the rear gunner Webb saw four depth charges strike the water to the starboard side of the U-boat and two on the her port side—another textbook straddling attack. Massive flumes of exploding water were seen rising on either side of the submarine, ten feet aft of the conning tower and totally obscuring the target.

Returning to the position of the flame float, Moore, Gibb and Ketcheson saw the U-boat in the bright moonlight, with a heavy list to starboard. As they approached, the bow rose steeply out of the water to an angle of about 80 degrees. The boat slid back into the sea “amid a large amount of confused water” according to the 224 Squadron ORB.

Moore circled in fascination and, coming around again, he turned on the powerful Leigh Light slung beneath his starboard wing outboard of engine No. 4. The blinding blue-white beam illuminated three yellow dinghies crowded with men floating on an oily surface strewn with bits of wreckage. One can imagine how exposed the survivors must have felt caught in the white light of the Leigh with a heavily armed Liberator thundering down its beam toward them. They passed overhead without further molesting the surviving crew, switched off the Leigh Light and left the German sailors floating in the moonlight.

The submarine was U-373, another Type VIIC boat commanded by Kapitänleutnant Detlef von Lehsten on its 11th war patrol. It had just slipped out of Brest after a six-month repair following a similar attack by a Coastal Command Wellington and Liberator in January. We know for certain that this was U-373 because all but four members of the crew survived to be picked up the next day by French fishing vessels and returned to Brest. Von Lehsten was one of the survivors.

Hat tip Al. First posted Sept. 2017.