When people think of the freed slaves and freemen who fought for the Union in the formations then known as United States Colored Troops (USCT), they often think of July 18, 1863, when the 54th Massachusetts stormed Fort Wagner.

Sadly, that more well known event - a Union defeat - overshadows an event six weeks earlier - a Union victory - that, at the time, probably had a greater impact on the growing support in the very racist by modern standards Northern Army to arming large formations of African-Americans than anything else.

The attack on Ft. Wagner and the 54th Massachusetts were both in the Eastern theater of operations. As such, they naturally get more attention. There is so much more to learn in the often overlooked Western campaign, just you need to try harder to find it.

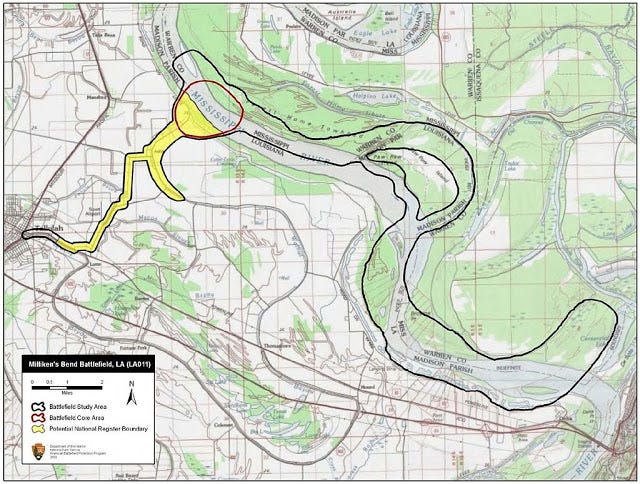

This FbF, I want to draw your attention to the Western theater and a battle on June 7th, 1863 known as the Battle of Milliken's Bend upriver from Vicksburg.

Let me set the scene.

You just immigrated from Switzerland to the USA seven years ago. Five years ago you were a private in this new army, and two years later you find yourself a Colonel.

You are commanding a supply depot as a side show of a side show of Grant's Vicksburg Campaign. You have a little over a 1,000 forces at your command. You are senior officer present, and with your command, the curiously named "African Brigade" by some, but to you are the 9th Louisiana Infantry (African Descent). They are almost all former slaves that you are told everyone knows will not make good soldiers.

The rest of your forces include the 23rd Iowa Infantry and 10th Illinois Cavalry.

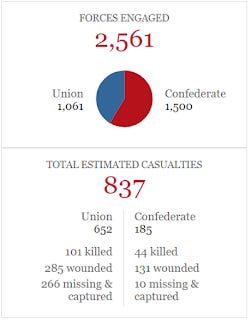

Facing you, with 50% more forces than you have - a brigade in Walker's Texas Division.

On the morning of June 6, Union Colonel Hermann Lieb with the African Brigade and two companies of the 10th Illinois Cavalry made a reconnaissance toward Richmond. About three miles from Richmond, Lieb encountered enemy troops at the Tallulah railroad depot and drove them back but then retired, fearing that many more Confederates might be near. While retiring, a squad of Union cavalry appeared, fleeing from a force of Rebels. Lieb got his men into battle line and helped disperse the pursuing enemy. He retired to Milliken's Bend and informed his superior by courier of his actions. The 23rd Iowa Infantry and two gunboats came to his assistance.

Walker proceeded east from Richmond at 7 p.m. June 6. At midnight, he reached Oaklawn Plantation, which was situated about 7 miles from Milliken's Bend to the north and an equal distance from Young's Point to the south. Here, he split his command. Leaving one brigade in reserve at Oaklawn, he sent one brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. Henry E. McCulloch north to Milliken's Bend, and a second brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. James M. Hawes south to Young's Point.

Around 3:00 a.m. on June 7, Confederates appeared in force and drove in the pickets. They continued their movement towards the Union left flank. The Federal forces fired some volleys that caused the Rebel line to pause momentarily, but the Texans soon pushed on to the levee where they received orders to charge. In spite of receiving more volleys, the Rebels came on, and hand-to-hand combat ensued. In this intense fighting, the Confederates succeeded in flanking the Union force and caused tremendous casualties with enfilade fire. The Union force fell back to the river’s bank. About that time Union gunboats Choctaw and Lexington appeared and fired on the Rebels. The Confederates continued firing and began extending to their right to envelop the Federals but failed in their objective. Fighting continued until noon when the Confederates withdrew. The Union pursued, firing many volleys, and the gunboats pounded the Confederates as they retreated to Walnut Bayou.

A small battle, with huge implications. It got the attention of the right people;

Grant praised the performance of black U.S. soldiers at the battle, observing that "This was the first important engagement of the war in which colored troops were under fire," and despite their inexperience, the black troops had "behaved well."

Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana wrote, "the sentiment of this army with regard to the employment of negro troops has been revolutionized by the bravery of the blacks in the recent battle of Milliken's Bend." Having seen how they could fight, many officers were won over to arming them for the Union. Even Confederate commander Henry McCulloch said the former slaves fought with "considerably obstinacy."

U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton also praised the performance of black U.S. soldiers in the battle. He stated that their competent performance in the battle proved wrong those who had opposed their service:

Many persons believed, or pretended to believe, and confidently asserted, that freed slaves would not make good soldiers; they would lack courage, and could not be subjected to military discipline. Facts have shown how groundless were these apprehensions. The slave has proved his manhood, and his capacity as an infantry soldier, at Milliken's Bend, at the assault upon Port Hudson, and the storming of Fort Wagner.

— Edwin M. Stanton, letter to Abraham Lincoln, (December 5, 1863)

While researching this I came across one story that bears mention.

One early recruit to join the regiment was named Jack Jackson. Jackson was said to be very large and strong-willed and quickly became a Sergeant in Company B. At some point Jackson joined the regimental recruiting parties; the officers were having trouble with convincing local field hands to join. Jackson's recruiting method was described as very forceful but ultimately successful.

At the Battle of Milliken's Bend one of Jackson's superior officers, Lieutenant David Cornwell, described the attack; saying that the 23rd Iowa was not behaving courageously but the three black infantry regiments offered great resistance. He said that Jackson, "Laid into a group of Texans... smashing in every head he could reach", and that, "Big Jack Jackson passed me like a rocket. With the fury of a tiger he sprang into that gang and crushed everything before him. There was nothing left of Jack's gun except the barrel and he was smashing everything he could reach. On the other side of the levee, they were yelling 'Shoot that big [_______]!' while Jack was daring the whole gang to come up and fight him. Then a bullet reached his head and he fell full on the levee."

It would be a great think if Jack and the rest of the forces that fought under Lieb could see the nation they brought in to the modern era.

It would be great to talk to them.

Fullbore.