Fullbore Friday

a village soaked in blood

The Russo-Ukrainian War of the last six months is reminding everyone - I hope - that war in a large measure does not change. Yes, some new technologies and ideas comes in that no one appreciates the value of until proven on the field of battle, some established technologies and ideas no longer work, and that process of integrating battlefield lessons often determines who gets better results over time.

At the end of the day, it is taking ground, keeping ground, and positioning yourself for more.

Thinking of that reminded me of a FbF from 4.5yrs ago that I thought I would bring back this week.

One of the enduring characteristics of WWI was the amount of blood that was shed over and over and over for such small bits of land.

So it was again in March of 2015;

French Commander-in-Chief General Joffre considered it vital that the Allied forces should take every advantage of their growing numbers and strength on the Western Front, both to relieve German pressure on Russia and if possible break through in France. British commander Sir John French agreed and pressed the BEF to adopt an offensive posture after the months of defence in sodden trenches. Joffre planned to reduce the great bulge into France punched by the German advance in 1914, by attacking at the extreme points in Artois and the Champagne. In particular, if the lateral railways in the plain of Douai could be recaptured, the Germans would be forced to evacuate large areas of the ground they had gained. This belief formed the plan that created most of the 1915 actions in the British sector. The attack at Neuve Chapelle was an entirely British affair – the French saying that until extra British divisions could relieve them at Ypres, they had insufficient troops in the area to either extend of support the action.

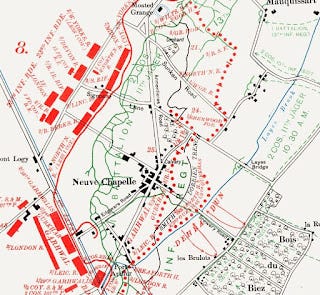

It is one thing to see the map of a battle as you see in the upper right hand part of the page - but here is a bird's eye view of the battlefield today. Driving through this now, it is an incredibly beautiful part of Europe - not the hellscape it was.

Neuve Chapelle village lies on the road between Bethune, Fleurbaix and Armentieres, near its junction with the Estaires – La Bassee road. The front lines ran parallel with the Bethune-Armentieres road, a little way to the east of the village. Behind the German line is the Bois de Biez. The ground here is flat and cut by many small drainage ditches. A mile ahead of the British was a long ridge – Aubers Ridge – barely 20 feet higher than the surrounding area but giving an observation advantage.

...

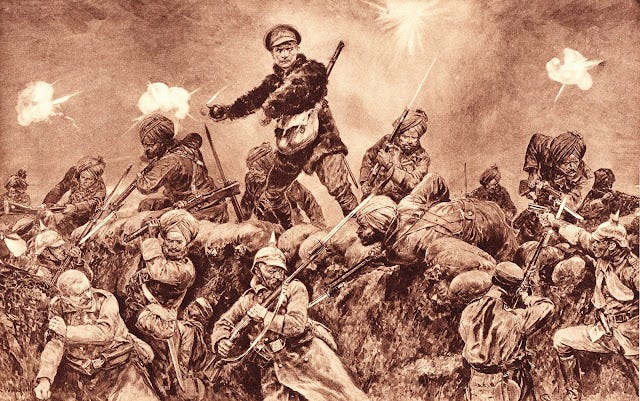

The attack was undertaken by Sir Douglas Haig’s First Army, with Rawlinson’s IV Corps on the left and Willcock’s Indian Corps on the right, squeezing out a German salient that included the village itself. The battle opened with a 35 minute bombardment of the front line, then 30 minutes on the village and reserve positions. The bombardment, for weight of shell fired per yard of enemy front, was the heaviest that would be fired until 1917.

...

Three infantry brigades were ordered to advance quickly as soon as the barrage lifted from the front line at 8.05am. The Gharwal Brigade of the Indian Corps advanced successfully, with the exception of the 1/39th Gharwal Rifles on the extreme right that went astray and plunged into defences untouched by the bombardment, suffering large losses. The 25th and 23rd Brigades of the 8th Division made good progress against the village. There were delays in sending further orders and reinforcements forward, but by nightfall the village had been captured, and the advanced units were in places as far forward as the Layes brook.

As was often the case in WWI - this 1915 battle was an experiment that hopefully informed future tactics. The price for this little wedge of land?

Casualties

The British losses in the four attacking Divisions were 544 officers and 11,108 other ranks killed, wounded and missing. German losses are estimated at a similar figure of 12,000, which included 1,687 prisoners.

...and the lessons?

It demonstrated that it was quite possible to break into the enemy positions – but also showed that this kind of success was not easily turned into breaking through them. The main lessons of Neuve Chapelle were that the artillery bombardment was too light to suppress the enemy defences; there were too few good artillery observation points; the reserves were too few to follow up success quickly; command communications took too long and the means of communicating were too vulnerable. One important lesson was perhaps not fully understood: the sheer weight of bombardment was a telling factor. Similar efforts in 1915 and 1916 would fall far short of its destructive power.

History tells us that we will again see larger-scale, heavy-casualty, nation-exhausting wars again. We are actually overdue for one. Like the decades of relative peace that followed Napoleon, so we too have enjoyed a long peace after the Cold War.

Human nature and habits are unchanged. This will come again, but when? Next week, next year, next decade? Where?

No one really knows, but what we can know is that it will most likely be a surprise. It will not be a short war. It will not be an easy war, and the world that comes after will be a foreign world than that existed before some nation's best and brightest thought they could control events.

Oh, and speaking of lessons, LongLongTrail forgot this one that History got. We'll see this again too;

The slowness and inaccuracy of communication between the front lines and the corps headquarters—the army had no wireless technology, and telephone lines at the front were usually cut or destroyed by enemy fire during battle—caused Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson, the corps commander, to order a fresh advance when support troops were unprepared. In the confusion, some artillery even opened fire on friendly infantry. By the late afternoon, forward units were attacking without adequate artillery support or effective coordination, in failing light, against a hardening German defense.

...

... it (was) incredibly difficult for commanders on both sides to know where and when to effectively deploy their reserve troops. General John Charteris, director of military intelligence under British commander Alexander Haig, took another sobering lesson from the battle, writing that “England will have to accustom herself to far greater losses than those of Neuve Chapelle before we finally crush the German army.”

Field Marshall Haig threw battalion after battalion at the First Battle of the Somme for four and a half months. Over that period, the British lost over 14,000 casualties per month. Haig and Lord Kitchener beat the “regimental traditions” drum over and over, where any truly competent military authority would have been questioning their equipment, tactics, or decisions. Charging uphill, while enfiladed by entrenched machine gun positions, in an artillery barrage? Or was it simple hubris by upper levels of the British command structure? I recommend “Men of 18 in 1918: Memories of the Western Front in World War One”, by a veteran of later fighting in that area, Frederick Hodges.

CDR, you said, "It will not be a short war. It will not be an easy war,..." True, but it will be <sold> as a short war. Or using the words of David Weber's Honor Harrington novel "A Short Victorious War." Putin thought his Ukraine War would be over in a month.