Fullbore Friday

caution can save you, or get you killed

Back in June we published the first of a three-part FbF from WWII that started in 2007 that many of the new readers have yet to enjoy, so if you didn’t get a chance to read Part-1 about that “glorious forgotten Fleet of the Damned“ - go click the link and come back.

Next week I’ll put up Part-3.

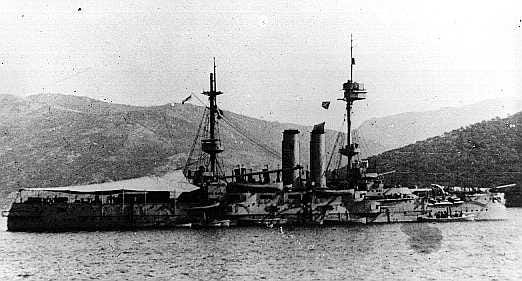

Time for Part 2 ... of 3 of the story of Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee' glorious and beautiful, but doomed fleet. It is time for a classic story of revenge at sea: The Battle of the Falkland Islands, 8 December 1914. I like to pay a lot of attention to HMS Canopus. If you review Part 1, you will see how you could dismiss this old ship full of Reservists; but is that what a leader does? No, a leader finds a way to make every bit of kit count.

On November 11 1914 the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible under Admiral Sturdee left for the Falkland Islands. HMS Princess Royal was dispatched to the Caribbean to guard the Panama Canal. The shock of the defeat at Coronel had made the Royal Navy take decisive action to destroy Spee and the battlecruisers were the chosen means for retribution.

After his victory Spee coaled and then loitered in the Pacific whilst he decided what to do next, little did he realise that this indecision would prove fatal. Eventually he decided to enter the Atlantic and try to make it home. The squadron had passed Cape Horn by December 1 and on the following day they captured the Drummuir carrying coal. They then rested for three days at Pictou Island. Spee wanted to raid the Falkland Islands but his captains were opposed to the idea, however in the end Spee decided to go ahead anyway, another decision he was to regret.HMS Canopus was now beached at Port Stanley, the capital of the Falklands, as guard ship. On December 7 Sturdee arrived, bringing the British warships at Port Stanley to the pre-dreadnought Canopus, the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible, the armoured cruisers Kent, Carnarvon and Cornwall, the light cruisers Bristol and Glasgow and the armed merchant cruiser Macedonia.

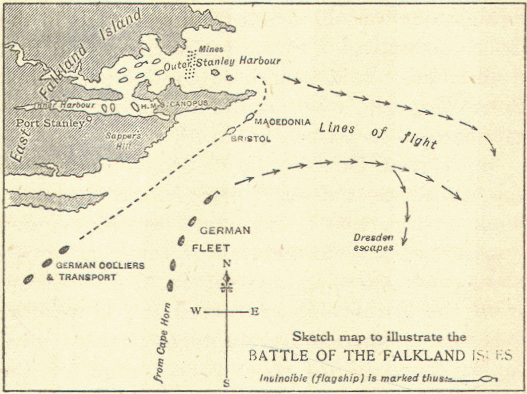

On the morning of December 8 1914 Gneisenau and Nürnberg were detached from the main squadron, which followed about fifteen miles behind, to attack the wireless station and port facilities at Port Stanley. At 0830 they sighted the wireless mast and smoke from Macedonia returning from patrol.

They didn't know that at 0750 they had been sighted by a hill top spotter which signalled Canopus which then signalled Invincible, flagship, via Glasgow. The British ships were still coaling and most ships, including the battlecruisers, would take a couple of hours to get up steam. If the Germans attacked the British ships would be stationary targets and any ship which tried to leave harbour would face the concentrated fire of the full German squadron, if they were sunk whilst leaving harbour the rest of the squadron would be trapped in port. Sturdee kept calm, ordered steam to be raised and then went and had breakfast!

0900 the Germans made out the tripod masts of capital ships. They were unsure of what theses ships were but they knew Canopus was in the area and they hoped that these were pre-dreadnoughts, which they could easily outrun.

Canopus was beached out of site of the German ships, behind hills but had set up a system for targeting using land based spotters. At 13,000 yards her forward turret fired but was well short, the massive shell splashes astonished the German ships who could see no enemy warships. The rear turret then fired using practice rounds which were already loaded for an expected practice shoot later. The blank shells ricocheted off the sea, one of them hitting the rearmost funnel of Gneisenau. The two German ships turned away. Canopus didn't fire again but she saved the British from a perilous situation.

Also a lesson on not pressing the attack and getting spooked. Probably remembering what happened when the British pushed the attack against his Squadron and were sunk for it - Admiral Graf Spee was too cautious by half, perhaps with a bit of "get-home-itis," a disease that will get you killed.

By 0945 Bristol had left harbour, followed 15 minutes later by Invincible, Inflexible, Kent, Carnarvon and Cornwall, Bristol and Macedonia stayed behind. The German squadron had a 15-20 mile lead but with over eight hours of daylight left and fine weather the battlecruisers would be in action in a couple of hours.

The German lookouts could now tell that the tripod masts belonged to battlecruisers which at c25 knots were considerably faster than the 20 knots the in need of refit German ships could manage. Spee set course to the South East in the hope of finding bad weather.

At first the British squadron stayed together but the battlecruisers were being slowed down by the other ships and so pulled ahead on their own.

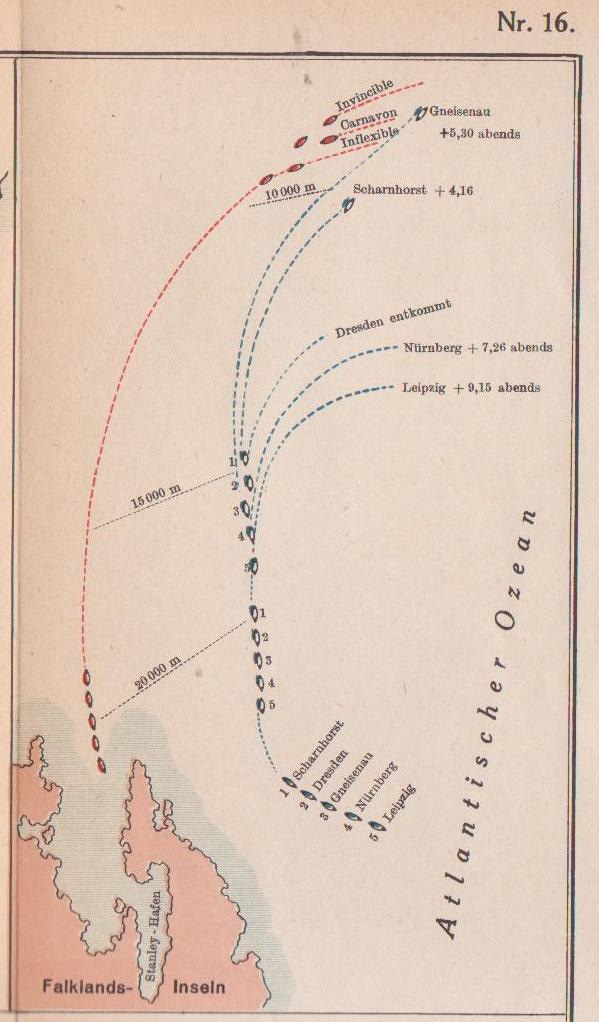

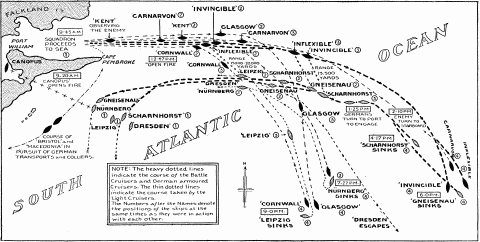

At 1247 at 16,500 yards the battlecruisers opened fire, with little accuracy, taking half an hour to straddle the rear ship, Leipzig. Spee realised he was caught and turned his armoured cruisers to slow the British whilst ordering his light cruisers to try and escape. Sturdee had made contingency plans for this and Invincible, Inflexible and the trailing Carnarvon engaged the armoured cruisers whilst the rest of the force set off after the light cruisers.

The battlecruisers turned onto a parallel course to Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at 14,000 yards. The Germans had the advantage of being in the lee position of the wind, the British gunnery was badly affected by their own smoke. The German shooting was excellent but at this long range their shells did little damage to the battlecruisers. The British also scored a few hits which did more damage but they were unaware of this as the visibility prevented them from seeing these.

In an attempt to gain the lee (smoke free) position Sturdee made a sharp turn to starboard towards Spee's stern. Whilst performing this turn the British were shrouded in their own smoke and Spee took this opportunity to turn south, pulling out of firing range. It took the British another 45 minute stern chase before they could resume firing.

At 1450 the battlecruisers turned to port to bring their broadsides to bear. Spee decided that his only chance was to close the range and use his superior secondary armament but his change of course made the smoke much less of a problem for the British. Their firing became much more accurate and both German ships, but especially Scharnhorst suffered severe damage and casualties. By had received over fifty hits, three funnels were down, she was on fire and listing. The range kept falling and at 1604 Scharnhorst listed suddenly to port and by 1617 she had disappeared. As Gneisenau was still firing no rescue attempts were possible and her entire crew including Spee were lost. Invincible had received 22 hits, over half 8.2 inch, but these caused no serious damage and only one crew member was injured.

Gneisenau kept on alone, zigzagging to the south west. At 1715 she scored her last hit on Invincible before her ammunition ran out. The British stopped firing soon afterwards and the burning German ship ground to a halt, her crew opening the sea-cocks and abandoning ship, 190 crew from a total of 765 were rescued but many of these died from their wounds. Inflexible was only hit 3 times and had 1 killed and 3 injured.

The brutal facts of war at sea. There is little room for caution or pause.

Whilst the big ships were fighting the smaller cruisers were having their own battles. The German light cruisers were in the order Dresden leading followed by Nürnberg and Leipzig whilst the British were led by Glasgow with Cornwall and Kent trying to keep up with her.

At 1445 Glasgow opened fire on Leipzig, Leipzig turning to port to reply, scoring two early ships whilst Glasgow's fell short. Glasgow had to turn away, allowing Leipzig to resume her earlier course. The other German ships had not turned to help Leipzig but had carried on their escape attempt.

Glasgow fired on Leipzig again, but this time the other German cruisers changed course, Dresden to the South West and Nürnberg to the South East. Glasgow's ploy of forcing Leipzig to turn and fire succeeded in slowing her so that at 1617 Cornwall had her in range, Kent setting off after Nürnberg.

Leipzig's firing was good but she didn't hit Glasgow and her shells didn't do much damage to Cornwall. By 1900 Leipzig's mainmast and two funnels were down and she was on fire. When her ammunition was exhausted she made an unsuccessful torpedo attack on Cornwall and then her crew prepared to abandon ship.

Glasgow closed the range to finish her off as her flag was still flying, stopping when two green flares were fired by the crippled German cruiser. At 2120 she rolled over and sank leaving eighteen survivors.

Cornwall had received eighteen hits but no casualties. Glasgow had received no damage after the two early hits which killed one and four wounded. Her boilers were damaged which reduced her speed enough for there to be no chance of catching Dresden which escaped.

Nürnberg had a 10 mile led on Kent and was, on paper, faster, but Nürnberg needed an engine overhaul and Kent's crew worked so hard that the old cruiser exceeded her designed horsepower, reaching 25 knots, being forced to burn all available wood on board and causing the whole ship to vibrate violently.

By 1700 the range was down to 12,000 yards and Nürnberg opened fire with the by now expected superb accuracy. When Kent returned fire ten minutes later her shells fell short. Once the range had fallen to 7,000 yards both sides started to score regular hits and Nürnberg gave up her escape attempt and turned to bring her broadside to action.

By 1730 the range was down to 3,000 yards and Kent's heavier shells and thicker armour gave her the upper hand. An hour later, just as bad weather arrived which may have saved her, two of Nürnberg's boilers exploded, reducing her speed. Kent was now able to easily outmanoeuvre her opponent and within half an hour Nürnberg was dead in the water, at 1926 she rolled over to starboard and sank with only twelve survivors.

Kent had received thirty eight hits but only sixteen casualties.

Whilst these battles had gone on Bristol and Macedonia had sunk Spee's colliers Baden and Santa Isabel, the other collier, Seydlitz escaped, eventually being interned in Argentina.

Even in victory, you will be second guessed by those who don't know; they just don't know but their petty concerns.

Sturdee searched for the Dresden before returning to the UK with the battlecruisers. There was some criticism (mainly from the 1st Sea Lord Fisher) of him for letting Dresden escape and for the heavy ammunition expenditure of his battlecruisers (Invincible 513 12 inch rounds, Inflexible 661 12 inch rounds fired) but generally his clear victory was welcomed. He had destroyed Spee's squadron without any serious damage to any of his ships and their shooting (c.6.5%) was considerably better than was managed by British (and German) battlecruisers at Dogger Bank and Jutland.

Ah, the SMS Dresden. That will be Part 3, with a twist. See you there in March.

NB: about five years ago they found the Scharnhorst. Just look at the lines of that ship when she was in her prime.

The story of von Spee's squadron is one of the great tragic tales of naval history. He was stuck quite literally on the other side of the world when war erupted. Meaning he had no realistic way to get home, merely to sell his ships and men as dearly as possible.

Which he did.

“Ares hates those who hesitate.” Euripides

It happens in all times. The nature of men and war doesn’t change much. Von Spee did his duty as best he could, as did Sturdee.

And public complaining about ammunition usage when winning strikes me as petulant. Use it effectively, but find what works and what does not!