My Grandfather's Navy, thanks to the good people over at the National Film Preservation Foundation.

Here’s the full video from 2015.

Well worth your time. Here is the background.

U.S. Navy of 1915 (1915)

Production Company: Lyman H. Howe Company. Transfer Note: Digital file made from a 35mm negative. Running Time: 11 minutes (silent, no music).

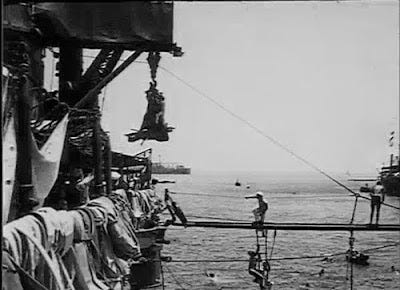

We are indebted to independent scholar Charles “Buckey” Grimm for identifying this 11-minute piece of the celebrated “lost” three-reel documentary U.S. Navy of 1915, produced by the Lyman H. Howe Company. (The piece had formerly been known only as “U.S. Navy Fragment.”) The film was made with the full support of the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, who believed in the power of motion pictures to convince isolationists of the importance of building a strong American navy. A former newspaperman who knew the value of publicity, Daniels allowed Howe’s camera crew remarkable shipboard access. The results show sailors as they go about their day—doing repairs, cleaning the deck, exercising, as well as demonstrating naval might. The film drew praise as capturing “the pulse-beat of the complex life that throbs through our dreadnoughts from reveille to ‘taps.’”

This was not first time the Navy had turned to film to tell its story. Early on, the Navy had collaborated with the Biograph Company on a now-lost series of 60 short films showing sailors and officers at work. The series screened at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair and 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland before being put to use in a Midwest recruitment tour. Naval facilities and ships also figured prominently in early newsreels and narratives. The service took care to ensure that depictions presented it in a favorable light and reserved the right, for commercial films shot with official approval, to reuse them for the Navy’s own purposes.

Buckey identified the fragment through careful detective work involving the ships and ordnance on display in the fragment. For example, the “E-2” class submarine, pictured in the opening scene, was taken out of service in 1915, and the shells mentioned in a intertitle—“It costs the U.S. government $970.00 for each 14 inch projectile fired”—were added to the naval arsenal the year earlier. The clincher was matching a frame from the documentary with an image used in a newspaper piece to illustrate the Howe film. Buckey reported his research at the 2010 Orphan Film Symposium at New York University.

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania in 1856, Lyman Hakes Howe got his start as a traveling salesman. In the 1880s he switched to lecturing and demonstrated a miniature working coal mine on the road. When movies came along, he was among the first to make the transition. He devised his own projector, the Animotiscope, which upgraded the Edison machine by adding a second reel, and playing a phonograph to add sound. Soon he was making his own travelogues and newsreels. Little survives of his output other than this fragment.

About the Preservation

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia generously lent the nitrate print to make the preservation copies. Edge codes on the source material date from 1917, suggesting this print of an earlier film may have been distributed to demonstrate American naval strength after the United States entered World War I. New prints are available at the Library of Congress and the NFSA.

My favorites? Swim call while taking on stores. PT - and the fact they worked in what we now call a dress uniform.

Hmm… So, $970 to fire a 14-inch shell? Back in the olden days, that would have grabbed attention, if not shocked people; it was an about year’s wages for an average working man or woman, down at the mine or mill.

.

In 1915, the value of gold was $20/oz…. And today, gold is around $1,940; or 97x change. So that $970 cost then translates into a current number of about $94,000, roughly. The price of a high end, luxury car. Or a big fraction of the price of a new house. Or way more than the US average household income of about $75,000 per year.

.

We don’t manufacture 14-inch shells anymore, obviously. But I’ve heard that new-production 155mm are costing out at about $4,000 each, all-in.

.

Everything has its own sort of sticker shock.

Thanks, Sal. If we don’t know where we came from, we have no idea of where we can go. With the exception of my father (AMM2, WW2), all of my ancestors were U.S. Army or state militia, but I can appreciate the difficulties of our 1915 Navy. I strongly recommend “Delilah” by Marcus Goodrich.