Usually for Fullbore Friday, I take a moment to either put out some good shipboard Gun Pr0n, find a little historical pearl, or tell again of those who fought at sea so maybe we can remember and learn what otherwise ordinary Sailors do to rise to the occasion to become extraordinary heroes. By remembering them and what they do, we keep the currency of their honor in circulation.

One thing about history that I have always found a bit sad, is that for each story we do know, there are millions that we do not. Lost to history, lost to those who took their stories with them to their reward.

In the comments section a while back, a reader mentioned the Gunboats of WWII. I remembered that comment when I was reading another bit on the Battle of Java Sea the other day and I remembered the USS Ashville (PG-21).

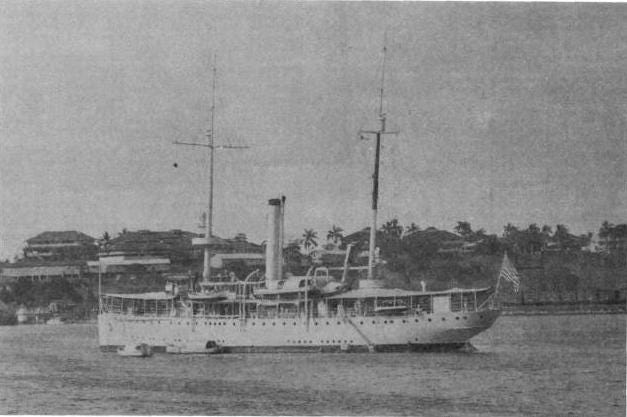

She was such a beautiful ship, as many of the Gunboats were. They looked more like a Robber Baron's yacht than a warship - but warships they were. Showing the Flag and serving in a Diplomatic role the Navy has always had. The USS Ashville had a great career, a great life that started towards the end of one World War, and would end at the start of another;

The first Asheville (Gunboat No. 21)—a single-screw, steel-hulled gunboat—was laid down on 9 June 1918 at the Charleston (S.C.) Navy Yard; launched on 4 July 1918; sponsored by Miss Alyne J. Reynolds, daughter of Dr. Carl V. Reynolds, MD, a prominent citizen of Asheville; and commissioned on 6 July 1920, Lt. Comdr. Elliot Buckmaster—who would later command the carrier Yorktown (CV-5) during World War II—in temporary command.

She had a storied, but normal gunboat life in Central America and China until WWII broke out. This is the tragedy.

Following the Japanese attacks on the Phillipines, Admiral Hart sent Asheville, and other surface ships, south from Manila Bay to the "Malay Barrier." By and large, only tenders and submarines remained in Philippine waters. Asheville stood out of Manila Bay a half hour into the mid watch on 11 December 1941, and, steaming via the Celebes Sea and Balikpapan, Borneo, ultimately reached Surabaya, Java, three days after Christmas of 1941.

She was eventually based at Tjilatjap, on Java's south coast. When Japanese planes bombed and heavily damaged Langley (AV-3) south of Java on 27 February 1942, Asheville was one of the ships sent to her assistance; she returned to port soon thereafter, the seaplane tender's survivors being picked up by other ships.

As the Allied defense crumbled under the relentless Japanese onslaught, however, the Allied naval command was dissolved. On the morning of 1 March 1942, Vice Admiral William A. Glassford, Commander, Southwest Pacific Force (formerly the U.S. Asiatic Fleet) ordered the remaining American naval vessels to retire to Australian waters.

Asheville—Lt. Jacob W. Britt in command—cleared Tjilatjap on 1 March 1942, bound for Fremantle. At 0615 on 2 March, Tulsa sighted a ship, and identified her as Asheville—probably the last time the latter was in sight of friendly forces. During the forenoon watch on 3 March, Asheville radioed "being attacked," some 300 miles south of Java. The minesweeper Whippoorwill (AM-35), heard the initial distress call and turned toward the reported position some 90 miles away. When a second report specified that the ship was being attacked by a surface vessel, however, Whippoorwill's captain, Lt. Comdr. Charles R. Ferriter, reasoning correctly that "any surface vessel that could successfully attack the Asheville would be too much" for his own command, ordered the minesweeper to resume her voyage to Australia.

Asheville, presumed lost, was stricken from the Navy list on 8 May 1942. Not until after World War II, however, did the story of her last battle emerge, when a survivor of heavy cruiser Houston (CA-30), told of meeting, in prison camp, Fireman 1st Class Fred L. Brown. Brown, 18 years old, had been in the gunboat's fireroom when a Japanese surface force (Vice Admiral Kondo Nobutake) had overtaken the ship on 3 March 1942. Destroyers Arashi (Commander Watanabe Yasumasa) and Nowaki (Commander Koga Magatarou) overwhelmed Asheville, scoring hits on her forecastle and bridge; many men topside were dead by the time Brown arrived topside to abandon ship. A sailor on board one of the enemy destroyers threw out a line, which Brown grasped and was hauled on board. Sadly, Asheville's only known survivor perished in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp on 18 March 1945.

We will never knew the story of her men, what they did for each other and for their ship - as they were all killed before they had a chance. The experience and stories by LT Britt and his crew will never be known - but think about that crew - because that is all they and the rest of the "Forgotten Fleet" of the Asiatic Fleet would want us to do. From the well-known USS HOUSTON (CA 30) to the USS ASHVILLE. They all did their duty while the rest of their nation woke up to finish the job that had to be done.

Speaking of gunboats.

One of the best movies of all time, The Sand Pebbles, has the best Flag Day Speech of all times. You can hear LT Collins' speech here. What he said.

What a great movie overall though - I know as a kid it got my attention. Come on, who wouldn't want to lead Sailors ashore armed to the teeth while wearing your Chokers? Who wouldn't want to lead your Sailors in battle with your sword in one hand and a pistol in the other, wearing the same?

Full fucking bore.

Our Navy has such an incredible tradition of valor, sacrifice, and devotion. I hope I’m alone in that I find it difficult to read stories such as the Asheville’s without feeling shame at what these men’s descendants (myself included) allowed the service to become. All we can do is to rededicate ourselves to the cause of restoring our navy and our military to a condition worthy of the sacrifice of those who came before us.

Full bore (presumably).

As for the Sand Pebbles look? We looked great in our chokers, but we were always jumpy as hell, moving carefully to avoid smudges and stains. Those things are a bear to keep clean.