Time to head back to the first decade of this blog for the second of a three-part Fbf focused on The Swan of the East. You can find Part-1 here.

There was a fox loose in your hen house - and no one can kill it

It is the beginning of WWI, and the RAN still flew the same flag as the RN.

When one thinks of WWI, one thinks of Flanders and Jutland; few think of the Indian Ocean. In 1914, there was a fox loose in the British Empire's hen house of the Indian Ocean - and she was a terror.

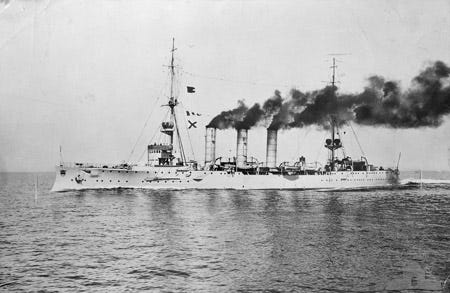

SMS Emden was launched in 1908, and became the Kaiserliche Marine'sTsingtao, in China, and was part of the German East Asia Squadron. On the same day as the Australian Government received notification that the Empire was at war, Von Spee's squadron was ordered to avoid the superior Allied naval forces in the Pacific, and it headed for Germany, by way of Cape Horn. The sole exception was the Emden, under Korvettenkapitänvon (Lt Commander) Karl Müller, which headed towards the Indian Ocean, with the objective of raiding Allied shipping. Müller frequently made use of a fake fourth smokestack, which — when the ship flew the Royal Navy ensign — made it resemble the British cruiser HMS Yarmouth and similar vessels.

The SMS EMDEN was detached from the East Asiatic Squadron for independent operations in the Indian Ocean. By early November Emden, under von Müller, Emden had sunk 30 Allied merchant vessels and warships. It had also shelled and damaged British oil tanks at Madras, in India. A collier named Buresk, was captured with its cargo intact, and was re-crewed with German seamen to accompany the Emden as a supply vessel. Other victims of the Emden included an obsolescent Russian cruiser and a French destroyer off Malaya, at the Battle of Penang, on October 28. By the end of October, no less than 60 Allied warships were looking for the Emden (the little outdated ship that was) .... forcing up insurance premiums, and drawing warships away from other theatres.

And so began the Battle of the Cocos.

On 9 November 1914 Emden landed a shore party at Direction Island to destroy the cable station. The operators managed to get off a warning signal before the station was closed down.

One last act before surrender. One last act by civilians who knew their place - but were gentlemen at the right time.

We quickly found the telegraph building and the wireless station, took possession of both of them, and so prevented any attempt to send signals. Then I got hold of one of the Englishmen who were swarming about us, and ordered him to summon the director of the station, who soon made his appearance, - a very agreeable and portly gentleman.

"I have orders to destroy the wireless and telegraph station, and I advise you to make no resistance. It will be to your own interest, moreover, to hand over the keys of the several houses at once, as that will relieve me of the necessity of forcing the doors. All firearms in your possession are to be delivered immediately. All Europeans on the island are to assemble in the square in front of the telegraph building."

The director seemed to accept the situation very calmly. He assured me that he had not the least intention of resisting, and then produced a huge bunch of keys from out his pocket, pointed out the houses in which there was electric apparatus of which we had as yet not taken possession, and finished with the remark: "And now, please accept my congratulations."

"Congratulations! Well, what for?" I asked with some surprise.

"The Iron Cross has been conferred on you. We learned of it from the Reuter

We now set to work to tear down the wireless tower. telegram that has just been sent on."

But that one signal - that one signal.

At about 0620 on 9 November, wireless telegraphy operators in several transports and in the warships heard signals in an unknown code followed by a query from the Cocos Island Wireless Telegraphy Station, 'What is that code'. It was in fact the German cruiser EMDEN ordering her collier BURESK to join her at Point Refuge. Shortly afterwards Cocos signalled 'Strange warship approaching.'

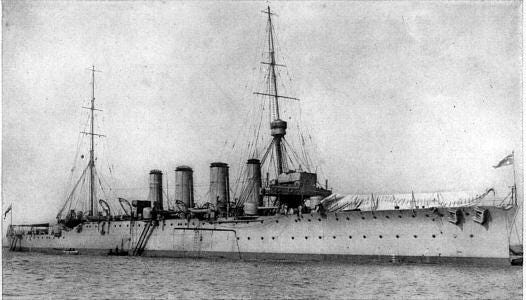

SYDNEY, the nearest warship to the Cocos group, was ordered to proceed at full speed. By 0700 she was 'away doing twenty knots' and at 0915 simultaneously sighted the island and the EMDEN some seven or eight miles distant.

Though SYDNEY didn't know what was going on, EMDEN's crew knew they were outgunned.

The RAN ship was a state-of-the-art Town class light cruiser, commissioned in 1913 and commanded by Captain John Glossop, an RN officer.

..

Sydney was larger, faster and better armed — (8) 6 inch (152mm) guns — than Emden, which had (10) 104mm (4.1 inch) guns.

She had to act fast.

EMDEN opened fire at a range of some 10,500 yards using the then very high elevation of thirty degrees. Her first salvo was 'ranged along an extended line but every shot fell within two hundred yards of SYDNEY.' The next salvo was on target and for the next ten minutes the Australian cruiser came under heavy fire. Fifteen hits were recorded but fortunately 'only five burst.' Four ratings were killed and several wounded.

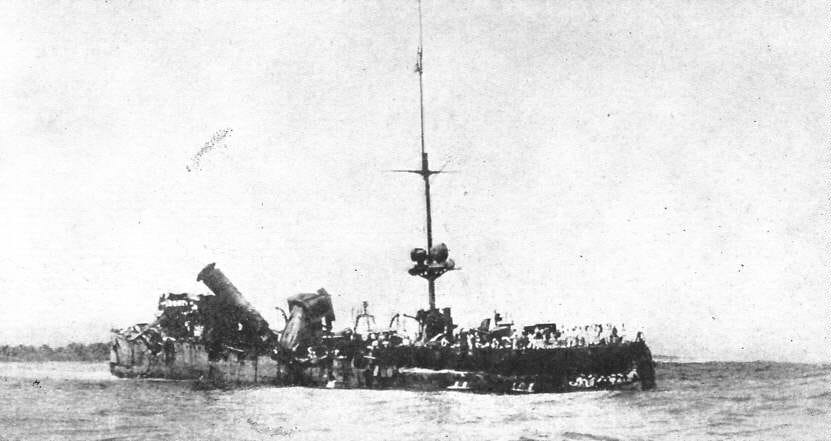

SYDNEY's first salvo went 'far over the EMDEN'. The second fell short and the third scored two hits. Meanwhile, EMDEN's captain (Captain Von Muller), aware that his only chance lay in putting SYDNEY out of action quickly, maintained a high rate of fire said to be a salvo every six seconds. It was to no avail. SYDNEY took advantage of her superior speed and fire power and raked the German cruiser. Her shells wrecked the enemy's steering gear, shot away both range finders and smashed the voice pipes providing communications between the conning tower and the guns. Shortly afterwards the forward funnel toppled overboard and then the foremast carrying away the primary fire control station and wrecking the fire-bridge. Despite the damage and the inevitable end, Muller continued the engagement. Half his crew were disabled until 'only the artillery officer and a few unskilled chaps were still firing.' Finally, with his engine room on fire and the third funnel gone, he gave the order 'to the island with every ounce you can get out of the engines.' Shortly after 1100, EMDEN was seen to be fast on the North Keeling Island Reef. She lost 134 men killed in action or died of wounds.

Look at that timeline for both ships. Also know, the SMS Emden had its CO ashore with a landing party of 50 out of a crew of 360. The XO took her into battle with a short crew - with no hesitation or delay - and aggressively.

There is one thing I would like you to do if you have time: go get a refill of coffee and read the following, including the full report at the link.

As we read the history of our Navy and others, there can be a tendency to think about ships and aircraft without really thinking about what a battle at sea can do to the men in them.

Dr Leonard Darby was the Senior Medical Officer of HMAS Sydney during her engagement with SMS Emden, and we have his notes. I will pull out some of the bits, but you need to read it all - and for you leaders out there - think about your Medical team. Your Corpsman. Your First Aid training for your crew. Are you ready for this?

By this time we had returned to the Emden, which was flying distress signals, and arrangements had now to be made for the transhipping and receipt of about 80 German wounded.

...

One German surgeon, Dr. Luther, was intact, but he had been unable to do much, and for a short time was a nervous wreck, having, had 24 hours with so many wounded on a battered ship with none of his staff left and very few dressings, lotions and appliances. The state of things on. board the Emden, according to Dr. Ollerhead was truly awful.

Men were lying killed and mutilated in heaps, with large blackened flesh wounds. One man had a horizontal section of the head taken off, exposing mangled brain tissue. The ship was riddled with gaping holes, and it was with difficulty one could walk about the decks, and she was gutted with fire. Some of the men who were brought off to the Sydney presented horrible sights, and by this time the wounds were practically all foul and stinking, and maggots 1/4 inch long, were crawling over them, i.e., only 24 to 30 hours after injury.

Practically nothing had been done to the wounded sailors, ... Some had legs shattered and just hanging; others had shattered forearms ; othes were burnt from head to foot; others had large pieces of flesh torn out of limbs and body. One man was deaf and dumb, several were stone deaf, in addition to other injuries. The worst sight was a poor fellow who had his face literally blown away. His right eye, nose, and most of both cheeks were missing. His mouth and lips were unrecognisable. The tongue, pharynx, and nasal cavity were exposed, part of his lower jaw was left and the soft tissues were severed from the neck under his chin, so that the face really consisted of two curtains of soft tissue hanging loosely front the forehead, with a gap in the centre, like an advanced case of rodent ulcer. In addition, the, wound was stinking and foul with copious discharge. The case was so bad that 1 had no hesitation in giving a large dose of morphia immediately, and after cleaning the wound as well as possible, a large dressing was applied, and he was removed to the fresh air on deck. The odour was appalling and it was some time before the sick bay was clear of it. The patient lingered from four to six hours afterwards in spite of repeated liberal closes of morphia.

Another face injury was almost as bad. Practically the whole right side of the face was completely blown away. His temporal, pterygoid, and maxillary regions were deeply exposed, and temporo-mandibular articulation was entirely removed. One had not time to examine these cases for minute details, but they were very instructive, and showed how hard it is to kill a man with face injury. In addition, the wound was septic and most offensive. I had no hopes for his life when he arrived, but he seemed to struggle on and five days later, on arrival at hospital at Colombo, it seemed likely that he would live. Later news tells us that the patient is doing well and they hope to fit him out with an artificial right half to his face.

...

Another face injury was rather severe. He had his right cheek turned down as a flap from the level of the upper lip, in addition the mandible was fractured and a piece of skin, fascia, and muscle the size of a large plate was blown out of the middle of the inferior surface of the left thigh. Later, when we were attending this case, it was suggested to me that the limb be removed. but though there was much destruction of tissue and the wound was very foul, I refused to allow this to be done and after events proved the wisdom of this, as the wound cleaned up and the limb was saved.

There were many cases of severe burns, two of which had head injuries in addition, and died on board. One of these was an engineer, who had suffered from pneumonia for six weeks on board the Emden. Altogether four deaths occurred on board us from among the German wounded. Most of the remaining cases had multiple lacerated shell wounds, with smaller or larger pieces of flesh blown away or penetrating tortuous holes, with metal buried in the tissue. Quite often this metal, was found just under the skin on the opposite side of the limb. Most of the wounds were charred. In one case a large amount of gluteal tissue was taken out in the region of the right anterior superior iliac spine, with fracture of the ileum. This man, in addition had a compound fracture of the right arm and numerous other wounds. A man was very lucky if he had less than three separate shell wounds. He was in a very low condition when we landed him, and it is doubtful if he will live.

In cases where large vessels of the leg or arm had been opened, we found tourniquets of pieces of spun yarn, or a handkerchief, or a piece of cloth bound round the limb above the injury. In some cases, I believe the majority, they had been put on by the patients themselves. One man told me he had put one on his arm himself. They were all in severe pain from the constriction, and in all cases where amputation was required, the presence of these tourniquets made it necessary to amputate much higher than one would otherwise have done, but no doubt their lives had been saved by the tourniquets. There was very little evidence of any skilled treatment before they arrived on board.

Naturally the German surgeon had been very much shaken and handicapped. His station in action was the stokehold, which was uninjured. His assistant surgeon was less fortunate, his station being the tiller flat aft, and when they were badly struck, fire broke out above him, whereupon he went up and was blown overboard, slightly wounded. The steering party remained in the tiller flat and were unhurt. After being blown overboard the surgeon managed to get ashore, and during the night he lay helpless and exhausted, dying of thirst, along with a few others who had also got ashore. After much persuasion he got a sailor to bring him some salt water, of which he drank a large quantity, and straightway became raving mad and died.

That, my friend, is war at sea. Most have forgotten. Hybrid-Sailors, "Optimal" manning, software run damage control and all that.And one last note, before they even got to the EMDEN, they had to treat their initial casualties. Why can't we have this in our Navy?

Cease fire sounded at 11.15 a.m. after we had been working two solid hours In confined atmosphere, and a temperature of 105 degrees F. The strain had been tremendous, and S.B.S. Mullins who had done wonderfully well with me, started off to faint but a drink of brandy caved him, and likewise myself.

Stay tuned for Part III next Friday.

UPDATE: Thanks to NEC338X, we have a great video to round out the story.

This is what you get with professionals--on both sides.

and no decent antibiotics. more misery and tragedy long after.

whatever else one may believe, war is hell.