Today we finish up Part-3 of a three-part series. If you’re just now joining us or want to review, at the links you can find Part-1 and Part-2.

When I first posted this in the fall of 2007 I kept thinking of your standard issue Navy Lieutenant we either were or served with. At the end of their first sea tour, close to about 27 years old.

What would a standard CO trust him with? Well, at war, you get responsibility fast.

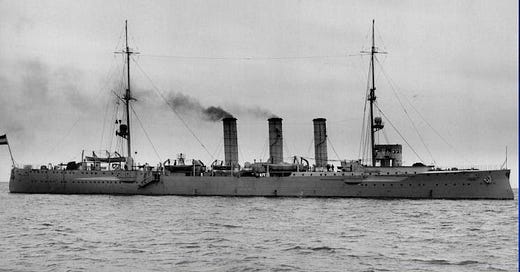

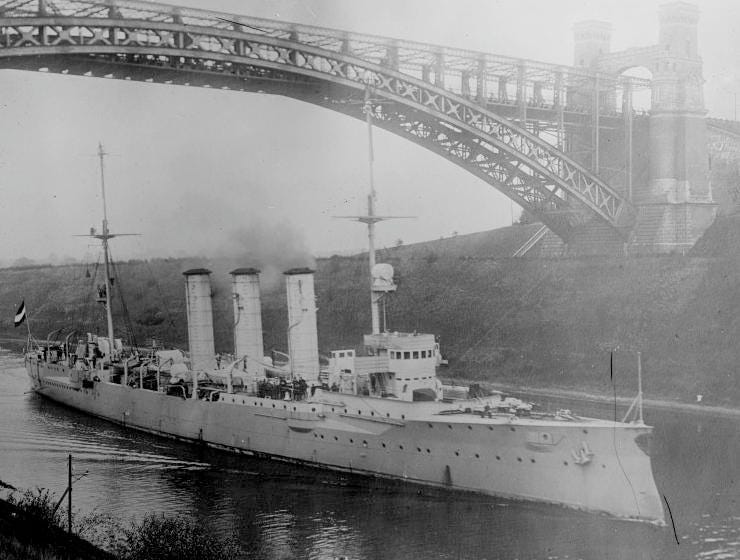

Fate. In time she catches all. Like her sister ship, the Swan of the East, she was a beautiful ship manned by the best there was. Finding herself and her sisters on the other side of the world from home and safety, surrounded by those who were hunting them and wanted them dead, they bravely headed through the gauntlet on the way home, knowing full well the odds - an epic tale.

On the way, she faced the fleet of the greatest naval power of her day and handed that power her first defeat on the High Seas in over 100 years at the Battle of Coronel. Turning the corner home, she found herself and her sisters, all five of them, spoofed, spooked, surprised, chased, fought, and defeated by that same power in the Battle of the Falklands Islands less than two months later.

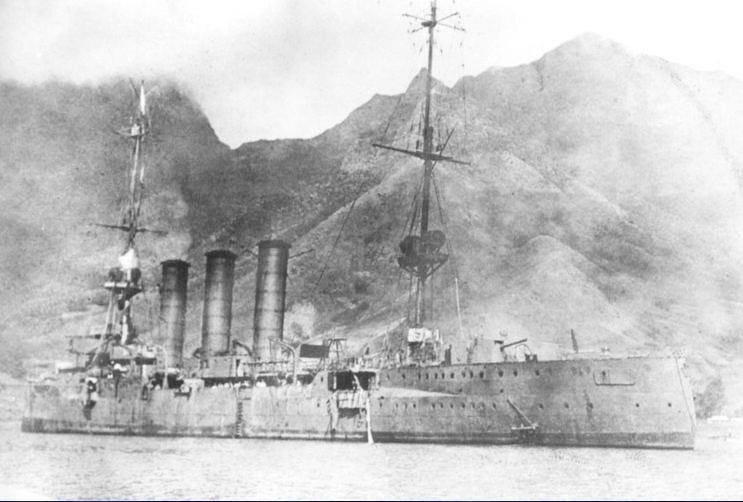

All her sisters are dead, and finding herself wounded and falling apart, she retreats away from the gauntlet waiting on her way home. Wandering as she finds a place to rest in the middle of nothing;

Approximately one month later, SMS Dresden was the only German cruiser to escape at the disastrous Battle of the Falkland Islands, her turbine engines proving faster than her expansion-engined squadron mates. The ship then headed south back around Cape Horn to the maze of channels and bays in southern Chile. Until March 1915 the ship evaded Royal Navy searches while paralyzing British trade routes in the area.

She waits. She waits for an old enemy, HMS Glasgow.

On March 8th, the Dresden put into the Cumberland Bight on the Chilean island of Mas-a-Tierra (AKA Robinson Crusoe Island). Due to a lack of supplies and parts for the worn-out engines, the ship ceased to be operational. Six days later, on March 14, 1915, British warships found the elusive German cruiser.

What do you do? The Commanding Officer, Kapitän zur See Fritz Emil von Lüdecke knew,

After a few shots were fired, the Dresden ran up a white flag and sent Lieutenant Wilhelm Canaris, who would become a famous Kriegsmarine admiral during the Second World War, to negotiate with the British. However, this was merely a ruse to buy time so the Dresden's crew could abandon ship and scuttle her. At 11:15 a.m. the Dresden slipped under the waves with her war ensign proudly flying. Her crew of about 300 men was interned in Chile for the duration of the war, with about a third electing to remain and resettle in Chile at war's end.

The right call, a good call. She and her crew could hold their heads high, including the one that later served in the Royal Navy. Made quite the diplomatic kerfuffle in its day, as reported by the NYT here.

Ok you smart types, look at that good LT's name. Yes, that Canaris - another story for another day.

I attended the Naval Heritage program about the 15th anniversary of the hijacking of the Maersk Alabama at Surface Navy Association the other night. One theme that came through was trust in your subordinates. One example was the CO of the Bainbridge who put two RIBs in the water to keep the lifeboat in international waters. Each had an Ensign in charge (although the CO said there was also a CPO to make sure the Ensigns didn't screw up).

Fullbore. Having been fortunate enough to have operated in that part of the world, these distant yet critical battles were not far from my mind. Of note, in recent years there have been several exceptional documentaries on the subject: https://youtu.be/lViz_siltm0?si=fJtATqJVFjYYqgdI