The “Out Years” is fantasy. It is a place where people wishcast the future they want.

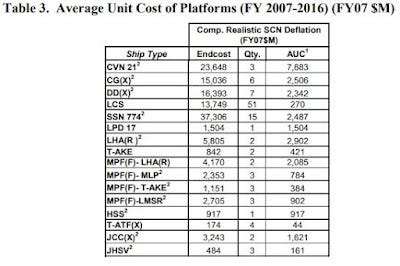

Let’s take a quick look at this gem from the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for FY 2007.

How'd that work out for us?

From that report looking forward nine years to 2016, it shows us having spent money on building in that time period … what exactly?

Seven (7) DD(X), aka DDG-1000, and six (6) CG(X).

Yeah … so be careful trusting these documents. That is why I simply refuse to listen to anyone’s pontifications on 2040 or 2045. Come on people. It’s insulting.

Let’s stick with that template of 9-years above, it's bad enough. From today that window would get us to 2031. Depending on who you talk to, that is either in the center or slightly right of center of the period expected to be the time of greatest danger with conflict over Taiwan with the People’s Republic of China. It also plays well with the issues we raised with the Hudson Institute’s Bryan Clark on Midrats last Sunday.

As men smarter than me have said, there are no magic beans. By the end of the decade there will be no “new” deployable program that will be able to change the fight west of Wake except on the margins in year-1 of any war. We will fight, +/-, at the end of the decade with what we have displacing water and making shadows on the ramp today.

There are things that we have right now – at or near IOC – that may, if given the proper resources and focus, be significant additions to our combat power by the end of the decade.

I’d point you to Sunday’s Midrats for a series of platforms and capabilities that fit that bill, but today I want to focus on one that really got my attention – mostly because it is a historically proven force multiplier, engines.

Throughout aviation history marginal existing aircraft were made good, and good aircraft made great simply by updating engines.

In recent history, two example stand out.

First the USAF re-engined its KC-135s;

The re-engined tanker, designated either the KC-135R or KC-135T, can offload 50 percent more fuel, is 25 percent more fuel efficient, costs 25 percent less to operate and is 96 percent quieter than the KC-135A.

On the Navy side of the house, there was the re-engined F-14;

Navy Secretary John F. Lehman Jr. went on to say the TF30 engine “in the F-14 is probably the worst engine-airplane mismatch we have had in many years. The TF30 engine is just a terrible engine and has accounted for 28.2 percent of all F14 crashes.”

…

In 1987, F-14s began receiving new engines in the General Electric F110, which offered more thrust and eliminated many of the reliability problems associated with the TF30. These improved F-14Bs and the subsequent F-14Ds were very much the Tomcat of Top Gun fame, and as a result, you’ll often find Tomcat fans dismissing the TF30’s woes as a problem specific to the F-14A in the early days of operation.

See the pattern?

What does this have to do with any future conflict with China?

The self-inflicted vulnerability of our airwing and its well-known retreat from range with a deck full of short-legged strike fighters with no organic tanking (sorry, buddy tanking does not count) needs to be fixed at sea or balanced ashore.

While there is a chance to get a fair number of deployable unmanned tankers by the end of the decade, that is about the only thing we have on the horizon. Mindless dithering, entitlement, and sloth means our new carrier capable aircraft won’t be ready for the fight.

What do we have that, possibly, might be able to help ashore for the USAF aircraft we will need beyond the finite number of heavy bombers and the delicate inventory of stand-off weapons they carry?

Though there are questions if it could be installed in the USN’s F-35C due to space constraints with the tailhook, and unquestionably can’t fit in the F-35B … for the land-based F-35A an engine replacement via the Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP) could provide a 25-30% increase in range.

Pratt & Whitney is testing its new XA101 Adaptive Engine Transition Program powerplant and expects to conclude testing its two examples by the end of next year, company military engines division president Matthew Bromberg revealed in an interview. He expects that two-thirds of the technology developed from AETP could find its way into earlier engines now flying with the Air Force.

The company is “thrilled” to have two options available for the Air Force and F-35 partners to choose from for an upgrade to the fighter’s propulsion system, Bromberg said. GE Aviation has developed the XA100 AETP engine as a competitor to Pratt & Whitney’s version.

Testing of “our first new fighter engine in 30 years … was successful,” Bromberg said. The first XA101 and its twin will shuttle back and forth between Pratt & Whitney’s facilities and the Air Force’s Arnold Engineering Center in Tullahoma, Tenn., for the next year or so, generating more data. The Air Force and F-35 Joint Program Office will use the data to help decide whether the F-35 should get an all-new powerplant—one of the AETP engines—or take Pratt & Whitney up on its offer of an enhanced version of the F135 engine already in the F-35 fighter.

Pratt & Whitney succeeded in achieving the AETP’s goals, which were to obtain 10 percent improvement in thrust and 25 percent improvements in both fuel efficiency and thermal management, Bromberg said. “We know we can do that,” he said.

Range and endurance is a primary driver for any conflict in the Pacific. If we need more range inside 5-10 year window, AETP is one of the few ways I can see it happening.

I can think of fewer programs ready to go that seem more critical if the USAF is going to be able to join the fray in a manner we need them to. The timeline is tight, but take what you can get.

Time is short … and so is the range of our aircraft.

All hail the F-35D.

I have pondered writing a reply, even though I am far from an unbiased observer. However, that bias is based on 25 years in the aerospace industry, with 16 years working propulsion systems, 9 years specifically on the F-35 propulsion system, the F135-PW-100/600. I worked on fuel systems, engine test, and flight test in the first decade of the program.

Looking at re-engining the aircraft is not too controversial., as CDR Salamander noted. The original engine, the JSF119, itself a derivative engine, first flew in late 2000 on the X-32 and X-35 aircraft. The F135, redesigned during the SDD (aka EMD) program, first flew in December 2006 on the CTOL AA-1 flight test aircraft. GE had a competing design funded through 2011, as the original concept was dual sourced engine, to revive the Great Engine War of the 1980s. Given that the JSF program was conceived in the 1990s and flew in the early 2000s, it is not surprising that propulsion, power, and thermal management requirements would change over 25-30 years of system development.

The first challenge for incorporating either AETP engine is the matter of security and exportability. The Joint Strike Fighter enterprise is an international effort, involving US DoD, services, multiple partner countries, and multiple FMS countries. The partner countries include United Kingdom, Netherlands, Australia, and Canada, nations with current or former interests in the Pacific. The FMS partner countries include Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, which are all located in the Pacific theater. These countries are operating F-35As and F-35Bs. The AETP engines, as designed today, can only work in the F-35As, and potentially F-35Cs. Due to the classification of the engine and US only clauses in contracts, the engine is only available to US services operating F-35As and possibly F-35Cs (if the Navy wants the complication). The security requirements will also have ripple effects across the aircraft as well as the maintenance and logistics for the aircraft.

This creates the second paired challenge of supportability and affordability (two of the original claims for the F-35, the other two being survivability and lethality). The security and physical construction leave both the USMC and multiple Allies out of the upgrade option and requires two separate engine production and sustainment efforts, which will increase propulsion production and sustainment costs for the enterprise.

The third constraint is likely time. While both GE and P&W were funded for technology development and engine demonstration programs, neither has been funded for a full EMD program. The engine designs must go through MIL-HDBK-516C for airworthiness (assuming no waivers from services, DOT&E, etc.), which will take time (years). New engine production lines must be created (years). New engine depots and procedures must be created (years). The program had a goal of no aircraft changes, but the classification requirements mentioned above will drive aircraft changes, at least software and procedures. This may limit the aircraft that can receive new engines further, slowing the creation and deployment of USAF squadrons with new engines.

P&W has a trivariant common upgrade for the F135 that increase range for all users, domestic and foreign. Changes to the power & thermal management architecture are available that could support growth in power generation and thermal management while reducing specific fuel consumption from any engine installed in the aircraft. GE could likely produce an upgraded version of the F136 to produce similar benefits, if dual sources for propulsion is desirable for the US and international user community.

Bottom line, if the USAF really wants AETP and funds it, industry will respond, but it will not be the right solution for the JSF enterprise.