There is always time to revisit the LCS program.

As we will continue to say, this must be reviewed over and over to the point it is ingrained in the minds of all present and future program managers and OPNAV staff weenies as an example and warning of what not to do.

Yes, the Front Porch has been warning about the trainwreck everyone is admiring today for about 18-years - we were almost exactly correct - but there are still people, important people, only now getting to the issue.

It is a busy world and well-meaning people assumed that the Navy that won the Cold War had enough institutional knowledge and inertia of excellence to properly develop the fleet of the future.

Oops.

Well, today over at Defense News, Noah Robertson has an excellent overview for those wondering how we’ve found ourselves in 2023 decommissioning ships that still have that “new ship smell” and haven’t even done a deployment.

Noah quotes a lot of Front Porch and Midrats favorites like Jerry Hendrix, to Bryan McGrath, Bryan Clark, and Bob Work.

Do read it all, but here are a few pull quotes for you to chew on;

It’s been called an “entirely new breed of U.S. Navy warship” and a “lemon.” A “mothership” for unmanned systems and “the wrong ship at the wrong time.” A cornerstone of the Navy’s “transformation” and the “little crappy ship.”

This is the littoral combat ship, which in its 22-year history has never been easy to label. That is until recently; the LCS has now become an enormous sunk cost.

Perhaps it would be petty for me to be a little butthurt that there’s no mention of “CDR Salamander” that along with that crusty yardbird Byron and a whole bunch of other members from the OG Blog Front Porch brought “Little Crappy Ship” in to common use before steel was even cut on LCS … but that’s OK. Everyone pretty much knows anyway, and like the old phrase goes - it is amazing what you can get done when you don’t care who gets credit.

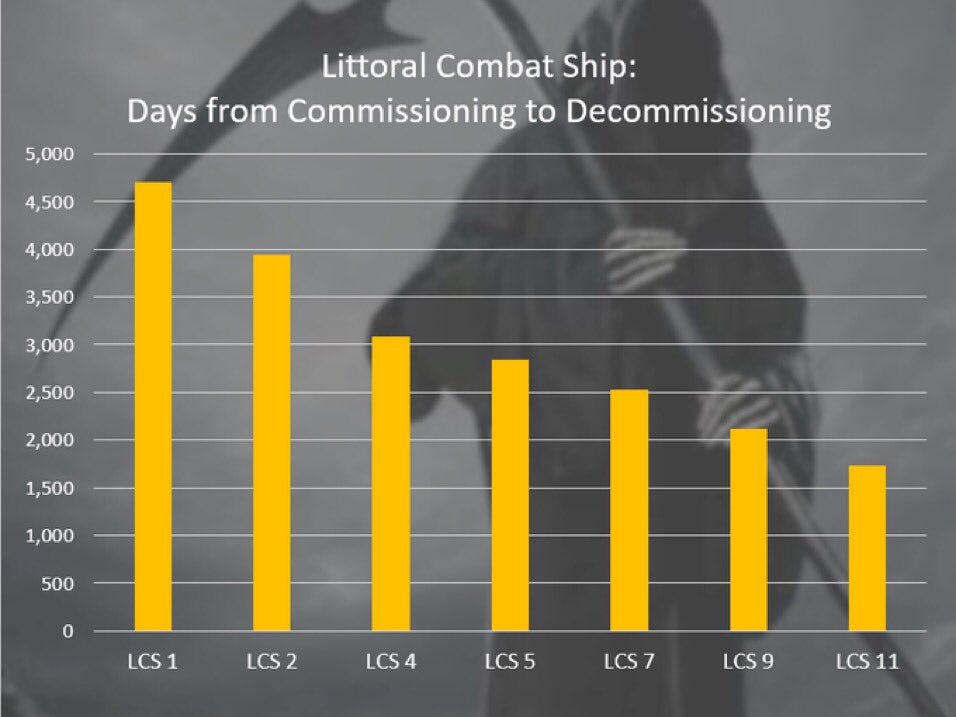

The Navy is decommissioning nine of 35 littoral combat ships in the next few years, alongside the five already abandoned. Some, like the recently retired LCS Sioux City, entered service less than five years ago.

For those who are not tracking, this graphic from Claude Berube last year is helpful (note: image updated via the irreplaceable Claude).

Decommissioning these ships early amounts to a loss of almost $7 billion based on analysis by Defense News using data from the Congressional Budget Office. But experts say the opportunity cost is more significant as the Pentagon prepares for a potential war with China, which in the last 20 years has built extensive anti-access, area denial defenses to keep ships like the LCS away from its shores.

Any economics major or someone who has run (successfully) a business will understand this decision. The issue with throwing good money after bad is a textbook case of “sunk cost fallacy” made by irrational and emotionally based people and organizations who promoted the wrong people to positions of authority.

But here we are…

“[These] ships were built for a world that no longer exists,” said Jerry Hendrix, …

Boghammar’s ghost haunted a generation of people. That had no small role in the effort to push LCS forward.

I’d like to have everyone remember my point above about “irrational and emotionally based.” What does that mindset do when they are told they are mistaken … that they are overreacting … that they are missing the big picture?

Well, that is pretty much what Big Navy did to its critics of not just the actual LCS ships proposed, but the entire series of CONOPS around it. From manning to mission modules, the wrong decisions just kept winning the argument.

But here we are…

“Decommissioning them is a terrible decision,” said Bryan McGrath, ... “But the only decision worse than that would be keeping them.”

That duality is our reality. Such are the fruits of our error and how the opportunity cost of LCS is such a critical part of the “Terrible 20s” stew where we need a larger fleet, we don’t have the money we need, demographics is playing havoc with recruiting, staff overhead is eating up institutional freeboard, macro-economic/budget realities are not responding, and what we spent a generation investing in simply is not producing enough juice for the squeeze we’re giving it.

“The idea [for the ship] was rather radical at the time,” said Bob Work, …. “What people don’t remember is this is something the Navy had never done before.”

No, that is not a full understanding of how this happened. “Mission Modules” were already a reality in some European navies. “Blue & Gold” crews were a reality in the submarine world and swapping crews in the surface force was measured and found wanting multiple times over the last few decades. It was not radical. What was radical was the complete handwaving of the lessons learned from them. Why were so many of us ringing the bells in the mid-00s when these CONOPS were making it in to open source? Because the history was known and intentionally ignored.

To lower personnel costs, the ship would have a condensed crew — less than 90 members compared to the 200 or so for a frigate. Hence, its sailors would need to be highly trained and make greater use of unmanned systems, which soon became a priority for the Navy as the Air Force began using Predator and Reaper drones in the Middle East.

The entire manning CONOPS was founded on the abuse of Sailors - “How long can we work these people non-stop until they burn out?” - and unworkable PPT-thick understanding of how you can have ships only manned by experienced Sailors. None of it was workable, but those who brought facts to the table were not invited back.

“Nobody wanted to say no [to these requirements] because this was an example of transformation,” said Clark of the Hudson Institute.

That was a command climate issue, in case you needed a translation of Bryan’s comment.

“What went wrong was the Navy couldn’t get the mission packages to work,” said Work.

That was the secondary result of the primary failure: we designed a ship around things that were PPT-thick and simply wished away technology risk. The poster child was the hubris that begat the never-was-has-been NLOS void.

The modular design — in which users could rotate equipment — was also proving impractical in terms of transporting the packages and quickly installing them. Furthermore, the specialized crews required for each mission drifted between ships, unable to gel with their vessel or their fellow sailors.

This problem was well known in the submarine community and was communicated to the highest levels before the first keel was laid. Again, this was hand-waved away in the arrogance that everyone involved in LCS was better than all previous generations.

“I don’t think we’re going to be decommissioning many that are all sunshine, no rain clouds,” said Mark Montgomery, a retired Navy rear admiral and a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies think tank. “I’m pretty confident that we’re decommissioning things that are maintenance burdens.”

Correct.

There is some utility in the Independence Class if for no other reason than their extensive available square footage and fewer mechanical issues, but the Freedom Class, especially the first couple of tranches, are simply lemons from what we’ve seen. See “sunk cost.”

What remains the best part of LCS?

The other success is the industrial capacity the program protected, according to Hendrix. By keeping two shipyards open, he said, the Navy maintained skilled workers. For example, the Marinette Marine shipyard in Wisconsin, which produced the rapidly decommissioning Freedom-class LCS, is now building the Constellation-class frigate, the Navy’s new small combatant.

Jerry is correct. It kept yards open that we simply cannot afford to be without.

How do we summarize the entire LCS experience now that we are in FY24?

Operating costs aside, the LCS program is still largely defined by its delays and waste. …

Still, the most significant waste for the LCS program may be a lost opportunity, Hendrix said. The time and resources spent building these ships could have gone toward building more capable and better-suited vessels for today’s threats.

Certainly the three missions of the LCS focused on countering anti-access, area denial capabilities, but that technology from the early 2000s has since advanced, rendering the LCS nearly useless against China.

…

“It’s a shame that we came to this realization after we bought all the ships,” the congressional aide said. “But I guess better late than never.”

Another reason why everyone needs to read “CDR Salamander” every day. If so, this staffer would have known - based on the average age of a congressional aide - some time in middle school.

In the end, even while we are trying to grow our fleet, decommissioning LCS is the right answer. This will free up sea duty BA/NMP that can be used to properly man battle force units that can fight west of the International Date Line, get more savings from ending unnecessary training pipelines, and probably even more important, allow maintenance money and infrastructure to go to the same useful battle force units.

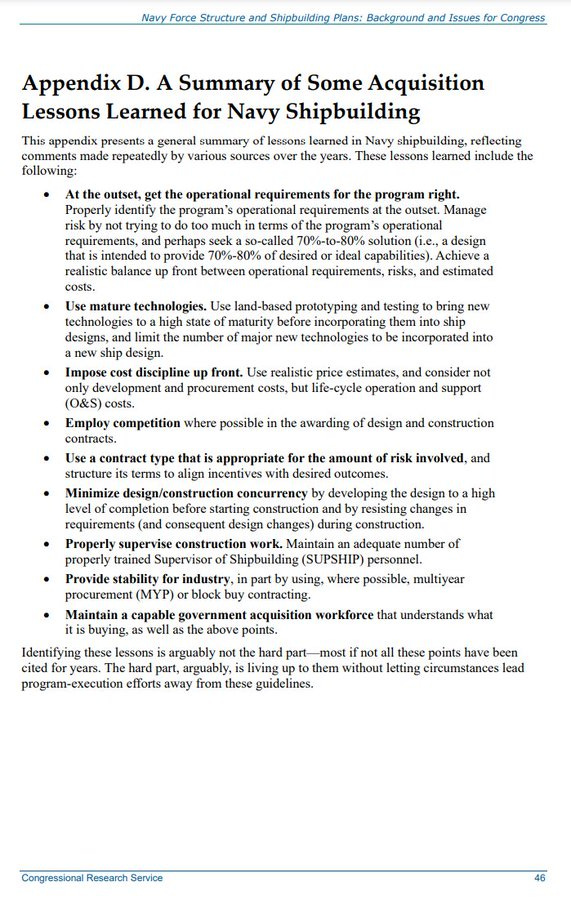

We also could keep a nice poster-sized copy of this jewel Charlie B. pointed us to:

Salute to CDR Salamander for his excellent efforts on bring these incidents to light.

Department of Defense material & equipment acquisition process has stopped being about providing the best product to the warfighter and has turned into providing the best process to whet the beaks along the way. Not only regarding the LCS program. There are numerous examples of the military boondoggles.

This has created a bloated expenditure system that helps civilian defense company executives and politicians acquire a vacation home on the lake, but the dysfunctional practice is to the extreme detriment to our military members and national defense overall.

10 years too late.