“Divest to Invest” is the lie a declining power tells itself when temporary leaders decide to shrug the hard work today to enable a more secure tomorrow, in order to have a comfortable and pleasant tour for themselves today – forcing others to have to play catch up later. It is that, or it is just plain wrong.

We’ve seen this play before in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and it failed so well last time, it is back again.

The Terrible 20s does not have to happen, but it is. Decline is a choice, and one we seem to be making … but it is reversible if a nation and its leaders have the will to stand athwart the declinist drive and yell, “Stop!”.

While it is easy to become frustrated, now is not the time to become demoralized. We are not in a dark room surrounded by the unknown – no – we are on a well-worn path.

We should start this week by having a visit with two old friends: Claude Berube and Jerry Hendrix.

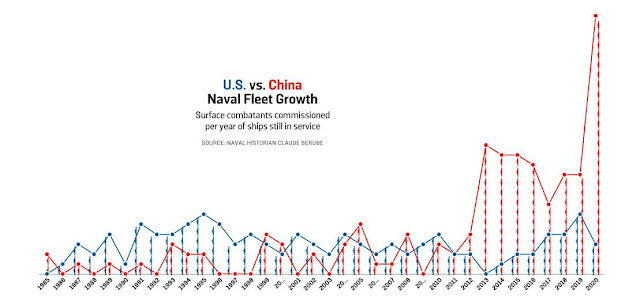

First, I’d like you to take a moment to look in detail at this essential graph from Claude. It speaks for itself.

Next, if you have not already, head over to Foreign Policy for Jerry’s superior ringing of the bell.

Now, with defense budgets flat or declining, leading Defense Department officials are pushing a “divest to invest” strategy – whereby the Navy must decommission a large number of older ships to free up funds to buy fewer, more sophisticated, and presumably more lethal platforms.

China, meanwhile, is aggressively expanding its naval footprint and is estimated to have the largest fleet in the world. Leading voices simultaneously recognize the rising China threat while also arguing that the United States must shrink its present fleet in order to modernize. Adm. Philip Davidson, who led U.S. Into-Pacific Command until he retired this spring, observed in March that China could invade Taiwan in the next six years – presumably setting the stage for a major military showdown with the United States – while Adm. Michael Gilday, the chief of naval operations, has argued that the Navy needs to accelerate the decommissioning of its older cruisers and littoral combat ships to free up money for vessels and weapons that will be critical in the future.

Taken together, these views add up to strategic confusion and an obliviousness to history.

…

Throughout history, large naval and merchant fleets represented not just a power multiplier but an exponential growth factor in terms of national influence. All historical sea powers recognized this – until they didn’t.

As I alluded to in the opening, we are not in uncharted waters. Other people and nations have been here before.

In October 1904, Adm. John “Jackie” Fisher was appointed first sea lord of the Royal Navy. He arrived in office certain who the enemy was – Germany – but also with clear direction from civilian leadership to tighten his belt and accept declining naval budgets. Fisher’s solution to this strategic dilemma was to dramatically shrink the fleet in order to pay for modernization while also concentrating the remaining ships closer to Great Britain. His investments in modernization were breathtaking – most notably the introduction of a steam-turbine, all-big-gun battleship, the HMS Dreadnought, which would lend its name to all subsequent battleships that followed, transforming global naval competition.

…

Today, Fisher’s strategy would be recognized as a divest-to-invest modernization plan. And the lesson is clear: Britain found that it was unable to preserve even the façade of being a global power; it was quickly reduced to being a regional maritime power on the periphery of Europe.

The ensuing conditions of international instability, shifting alliance structures, and the global arms race contributed to the outbreak of World War I and the end of empires, including Britain’s.

There is a comfortable delusion a navy at peace can fall in to; filter upon filter takes out the hard answers to difficult questions – giving favor to soft, comforting answers resting on a platform supported by delicately crafted, untested, and fragile assumptions.

…the overarching U.S. naval strategy, stated repeatedly by defense leaders during this spring’s round of congressional hearings, is to “divest” of older platforms in order to “invest” in newer platforms that, although fewer in number, would possess a qualitive edge over those fielded by competitors. As history reveals, this strategy will produce a fleet too small to protect the United States’ global interests or win its wars.

When soft answers gain too many advocates, it steers the nation into dangerous waters. That is when the hard answer advocates must raise their voices.

To avoid the mistakes of the past, Congress should follow its constitutional charge in Article 1 and allocate funds sufficient to both provide for a newer, more modern fleet in the long run and to maintain the Navy that it has today as a hedge against the real and proximate threat from China. Such an allocation requires a 3 to 5 percent annual increase in the Navy’s budget for the foreseeable future, as was recommended by the bipartisan 2018 National Defense Strategy Commission.

Both steps are crucial. Weapons like hypersonic missiles and directed energy mounts like the much-hyped railgun are changing the face of warfare, although not its nature, and the United States must invest to keep up with its competitors in China and Russia, which are already fielding some of these systems in large numbers. … Great powers possess large, robust, and resilient navies. Conversely, shrinking fleets historically suggest nations that are overstretched, overtasked, and in retreat. Such revelations invite expansion and challenge from would-be rivals. To meet the demands of the current strategic environment, the U.S. Navy must grow – and quickly

…

Now, in this third decade of the 21st century, the United States must not ignore the rhymes of history, repeating the mistakes of the sea power that came before it – Britain – by lulling itself into the false belief that it can divest to invest in a brighter future while China maneuvers to overtake it. It must have larger defense budgets that will allow for a sea power-focused national security strategy in the face of rising threats. The United States must recognize yet again – as other have before it – that on the world’s oceans, quantity has a quality all its own.

The United States is a maritime and aerospace power. A strong maritime strategy is a strong national strategy. Say it. Speak up. Repeat until you tire of the argument, then repeat it more. Support those who do likewise. This will take a while.

Like the next war, this is will be a long fight.

It’s not ships but leaderships that matter and we have been bankrupt for a generation or two, navy failures have become generational.

Where is the Carl Vison of 2020's, who will come up with the Two (Three) Ocean Navy Build Plan?