While doing showprep for yesterday’s Midrats with Bryan McGrath, I came across a post that in my mind was put up not all that long ago, but in reality was put up just a couple weeks shy of a decade ago, 14SEP2014. Time flies, etc.

It kind of fits a theme that has kept coming up the last few weeks: yes we have challenges and unresolved issues … but few of them are new.

So many of the problems we have now are a subset of a larger cultural defect: rewarding problem appreciation and holding no one accountable for not taking action.

Anyway, as I could write almost exactly this same post today as I did ten years ago - that says something. I’ve not changed a word, so especially with the info on Jerry, it is a decade old. Enjoy the time travel.

As for what that the lack of change in a decade, give it a read and let me know your thoughts about what exactly why we’re still stuck.

Oh, and yes - I am quite enamored with my graph.

I love think pieces, the ones you read that make you stop, read again, and then parse.

Find the chaff, define the wheat, and then shuffle again - breaking in to bits.

Fresh off his civilian clothes shopping spree now that the uniform is in the back of the closet, our friend Jerry Hendrix, CAPT USN (Ret.) is stretching out his PhD on his new desk at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) in a bit at The National Interest that is well worth you stopping by to read in full; A Conservative Defense Policy for 2014: Look to Eisenhower.

In my first run at Jerry's bit, I was a bit drawn off what I think are some unnecessary distractions. I think they are there because this probably should have been broken in to a few articles. Valid topics worthy of discussion, but perhaps best in a separate article.

The first distraction was the opening partisanship vibe it gave off - right away it puts up walls to half your readers if they imply what follows is another (R)-bad (D)-not bad bit;

Recent discussions amongst Republicans regarding U.S. Defense force structure have revealed an ongoing disagreement between two camps within the party. Military Hawks, citing the recent disturbances in Ukraine and Iraq, have begun to beat the drum for more resources to be allocated for the Department of Defense to address threats that never really subsided. Fiscal Hawks, focused on budget deficits that stretch as far as the eye can see, continue to argue for DoD to continue to be part of a basket of cuts in entitlements and discretionary programs.

That is a good argument to have, but why limit a two-sided debate to one party? No reason to make this seem partisan to some readers, you have to draw in the inside argument for the other party - there is one if you look for it. In any event, Republicans only have one-half of Congress - they aren't even a majority decision maker. The Democrats hold most of the power levers, especially holding the Commander in Chief billet, that are the key in making any significant decisions in defense.

Maybe it is just me and my ongoing theme of the need to find and nurture a bi-partisan defense consensus. There is one, but we keep missing opportunities to feed it - I'm a little sensitive to the topic.

Sure, there are extremes on defense in both parties that will never learn good sandbox skills for the benefit of all - but there is a large group from both sides of the aisle whose interests well overlap and are the key to finding the right answer to a very real challenge.

In his article, Jerry only brings up the Democrats directly in this context;

The Democrats need to come to the table to address the looming crises in Social Security and healthcare.

Yes, they do - but so do Republicans. By not at least addressing the internal debate in both parties on defense and entitlement spending, an opportunity is missed by putting Republican interest in defense and Democrat interest in domestic issues - the actual situation is much more nuanced. Lost opportunity and a distraction, but let's move on.

I would offer that this one aspect of the article should be set to the side whether you enjoy it or not, because Jerry is bringing up some reference points that are spot on and should be the part of all efforts to find the right solution;

It has not been so long since the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff pronounced that our debt posed a grave threat to our national security at home and around the world.

...

we should not give way to election-year desires to spend more, ignoring the long-term implications of our debt.

...

In the end, a major inflationary pressure remains our addiction to exquisite platforms.

There he hits it. Regulars here and at Midrats know this is a topic that is absolutely critical. "Exquisite," "Tiffany," "Perfect vs. Good," "Transformational!," - the Biblical plagues we have suffered over the last couple of decades. Regardless of how we got here or who is at fault, it needs to be fixed now.

This is where my review of Jerry's article turns. He sets out an argument that is incomplete but central, and a valid starting point;

... the United States needs to maintain a military strong enough to deter the rise of competitors and preserve its ability to respond to crises around the world, the question that remains is: how large and how capable does our military have to be to accomplish these twin goals?

I don't think a strong military will deter the rise of competitors, just as Rome did not deter the Germanic tribes or the British Empire deterred Imperial Germany - but a military does need to be strong enough to decisively meet any challenge at war while being effective and affordable in peace, or at least a warm peace. (NB the word "strong" does not necessarily mean "big" - more on that in a bit).

Objective analysis suggests that a path exists that would allow cuts to the DoD budget and marginal growth in the force. Such a path is predicated on recognizing that our national fascination with high-tech weapons systems has led to a defense culture where the exquisite has become the enemy of the “good enough.”

There it is. That is the core; that is the question - that is the sexy bit.

Is that a path, or a destination - or both? How do you visualize the quandary that less can give you more, and that to meet a nation's national security requirements - more might actually be less?

Is it as simple as quality vs quantity? Platforms vs. payloads? Size vs nimbleness? Yes and no.

How do we boil that down? For me, I go back to my other calling; economics.

Economics is the perfect meeting place between the hard and soft sciences - the STEM and the philosopher. Yes, self-serving observation, but it is my blog, so roll with me a bit.

I will make an assumption - you all know what the Laffer Curve it. If not, read up and come back.

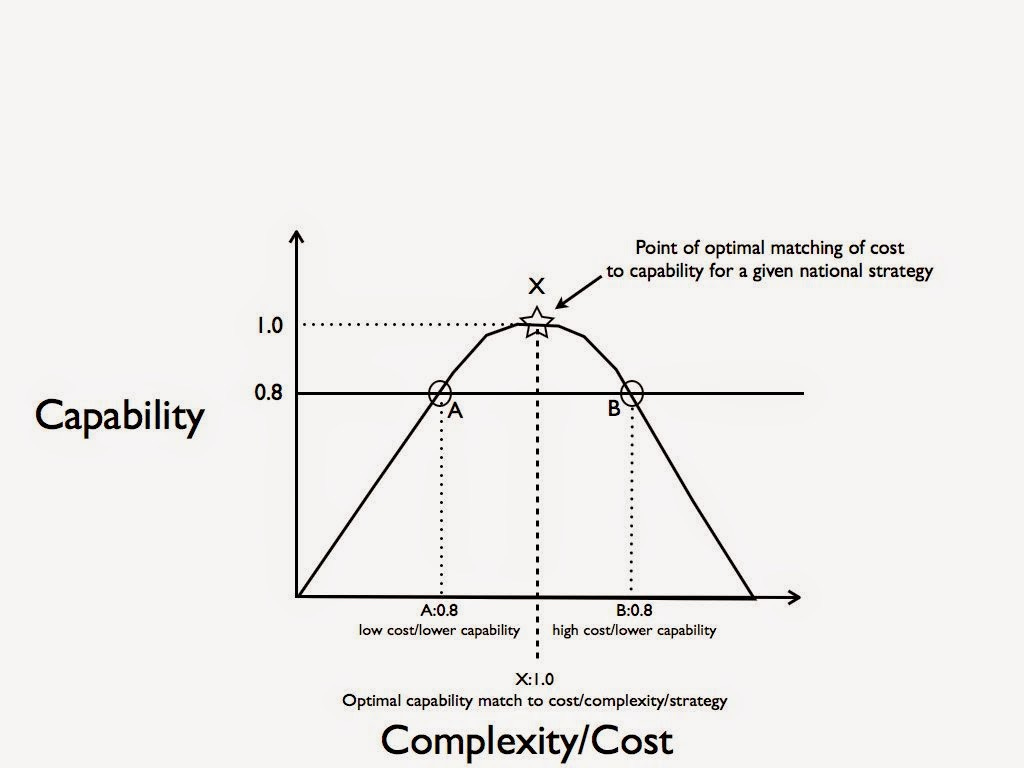

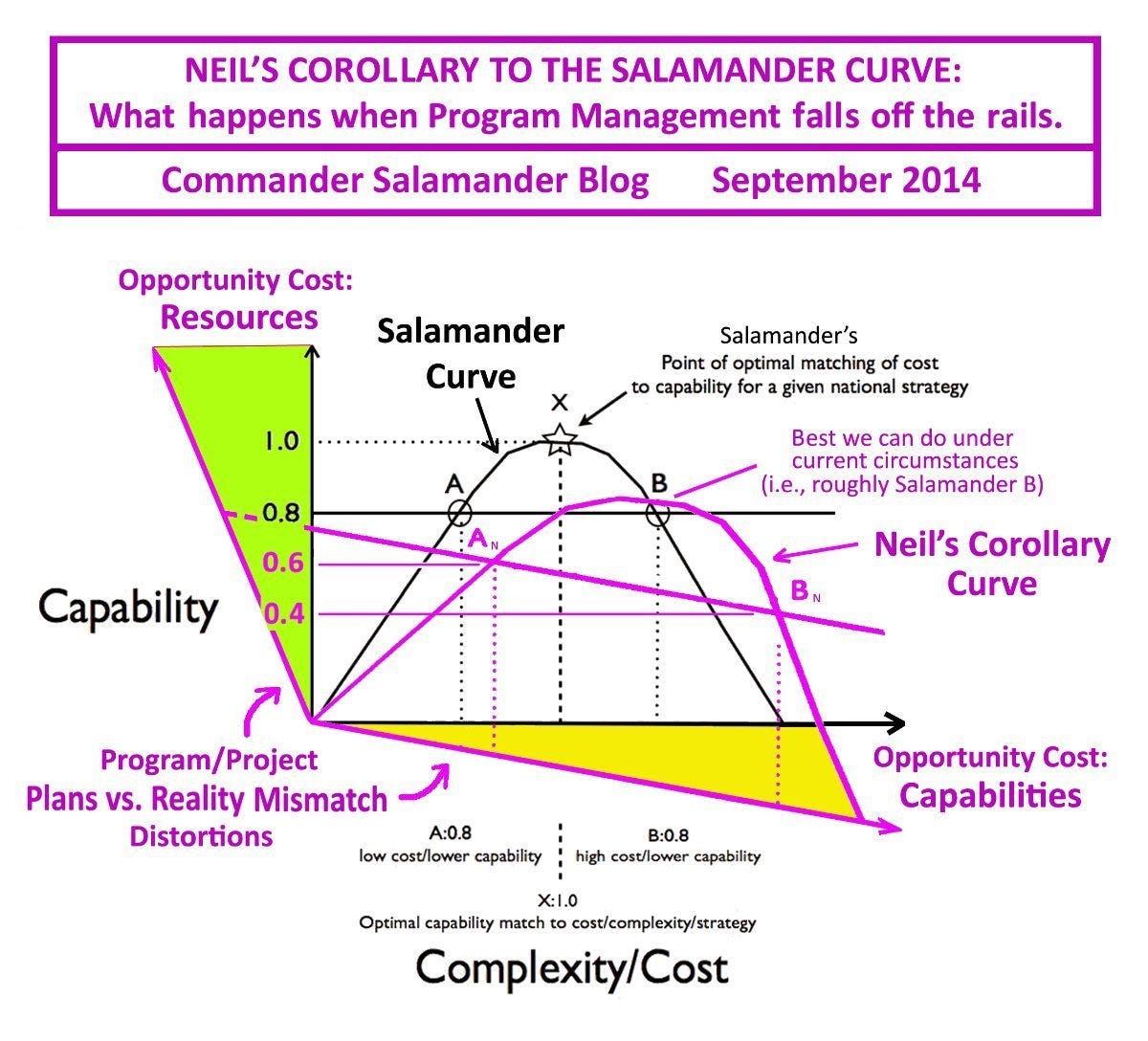

If you are looking for my takeaway visual for most of what Jerry is looking for and trying to explain - here you go. Let's call it the Salamander Curve. Ahem ... OK, the Salamander-Hendrix Curve ... ehhhh, alright then; Hendrix-Salamander Curve, whatever ...

Executive Summary: for every national security military requirement (X), there is a place where the maximum benefit is gained between cost, complexity, and utility. The challenge is to find that maximum benefit. On either side of that point, you are operating at a suboptimal level; either you are spending too much on too much complexity and producing a diminishing level of capability to the nation, or you are spending too little on obsolete or sub-optimal platforms to achieve what is required. Depending on where you are, you can spend more on more complex systems and personnel and gain additional national security benefit, or you can spend more and get less.

Jerry put it, perhaps, a bit more eloquently.

It is unwise to accept the false premise that we can only arrive at a larger force by spending more on the same types of platforms that we are already building. A conservative approach to the future must find the right balance between high-priced silver bullets that can only be purchased in small numbers and low technology assets that can be purchased in large quantities at low costs. ... The turning point on defense will occur when we recognize that spending less money does not have to equate to a smaller force. Wise leaders have a credible alternative in defense-force structure and should pursue it.

UPDATE:

CDRSalamander has the absolute best comments section out there. So good, I have to bring it in to the main post.

The difference between using a Laffer Curve for defense and taxation is that taxation can be measured without a disaster, while defense, if you get it wrong, will turn into a disaster.

Add to this that, while none of the very measurable things are very important, none of the very important things are very measurable.

There seems to be a misperception about debt among conservatives.

Debt is neither good nor bad. It's all a matter of what you are borrowing for and your ability to pay it back.

There is a difference between borrowing money to go to medical school and become a surgeon vs. borrowing money to have a good time in Las Vegas.

There is a difference between borrowing money to repair US95 from Miami to New England vs borrowing money to turn Afghanistan into a Jeffersonian democracy complete with Pride Week.

As for liberals, they assume that debt is never a problem because you can always print money to pay it off and anyway life is beautiful in Georgetown, Aspen and Martha's Vineyard.