For those are wondering if this sounds familiar, well, you know your history.

A panel of experts appointed by the United Nations to monitor the Houthis' military evolution seems to think they might be. In a report for the UN Security Council in October, the experts write that the Houthis may have started charging ships going past the Yemeni coastline millions for guarantees that they won't be attacked.

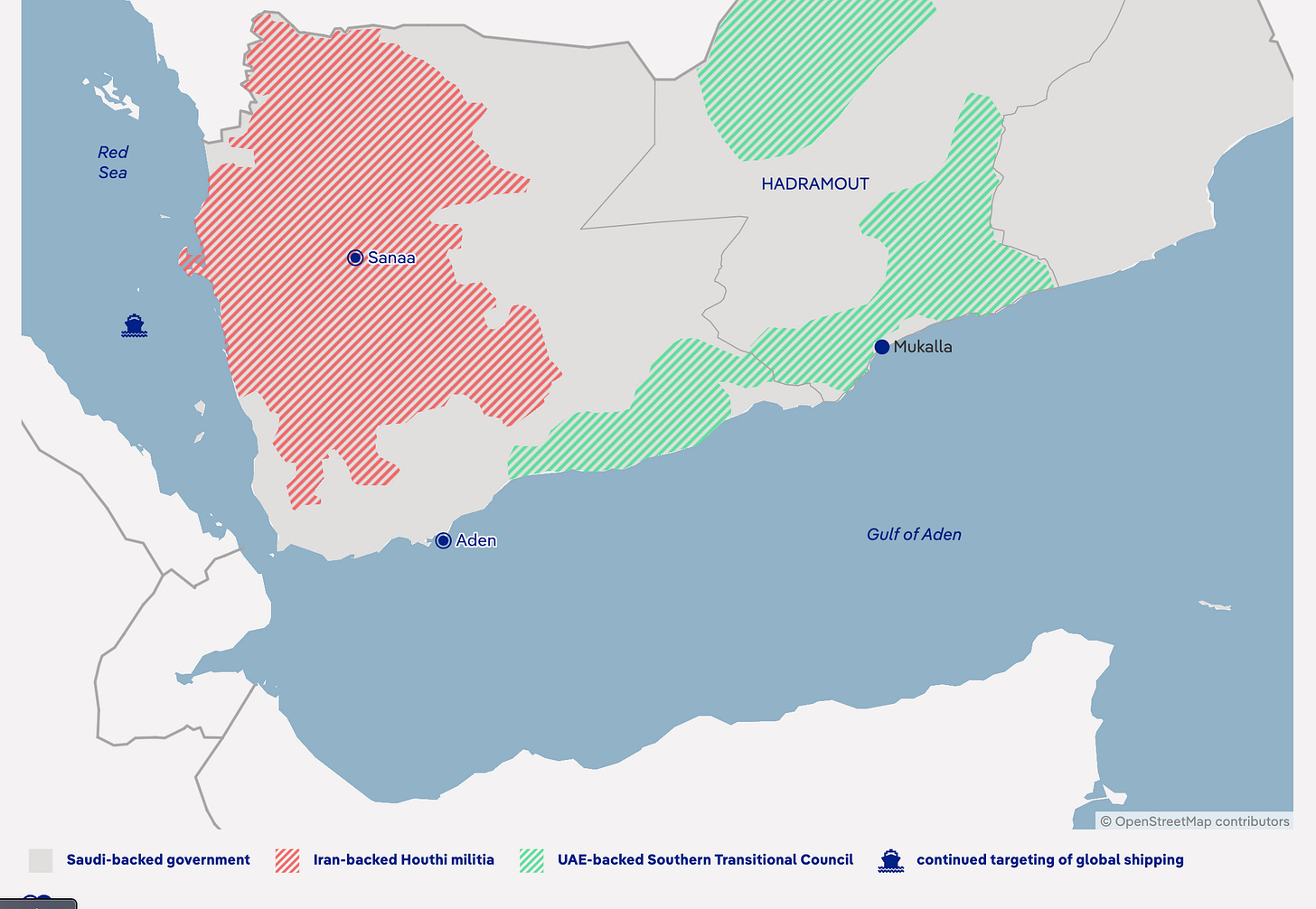

The Houthis have been firing rockets at maritime traffic off Yemen's coast since November last year. The rebel group, which controls most of northern Yemen, says it is doing this to back the Palestinians and to fight against Israel and the US, whom they consider enemies.

"The Houthis allegedly collected illegal fees from a few shipping agencies to allow their ships to sail through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden without being attacked," the UN report says, quoting anonymous sources. "The sources estimate the Houthis' earnings from these illegal safe-transit fees to be about $180 million [€169 million] per month."

This money is transferred to the Houthis via the informal network of money transfers known as "hawala," the report continues.

These fees could add up to about $2.2 billion (€2 billion) a year and would be one of the Houthis' largest income streams. They might also give the group a financial incentive to continue their attacks, no matter what happens in Gaza and Lebanon, observers say.

Don’t forget, we are not talking all of Yemen, nor all that much coastline.

At some point, we will know who is paying tribute, but as for the USA … we’ve been down this road before. We even have songs about it.

The state-sanctioned Barbary corsairs had been raiding European commerce for centuries and sustained their treasuries with tribute paid in exchange for unfettered passage. Without the protection of the British Royal Navy, U.S. merchants faced seizure along the length of the Mediterranean.

…

In October 1784, Moroccan corsairs, acting on behalf of the Sultan of Morocco, Sidi Mohammed ben Abdallah, seized the U.S. merchant ship Betsey as it departed the Mediterranean on a return trip to the United States. Though Moroccan corsairs had a long and notorious reputation for seizing shipping in exchange for tribute and crew ransoms, this capture was specifically intended to bring the Americans to a peace and trade treaty. Sidi Mohammed ben Abdallah had decided that the benefits of trade with the Americans amid the volatility of Europe would outweigh that of tribute and possible reprisals.

The United States agreed, and the Moroccan-American Treaty of Peace and Friendship, also known as the Treaty of Marrakesh, was signed in 1786. Flush with success in resolving the first of these obstacles to free trade, Americans authorities hoped to create similar treaties with the other Barbary States. Those hopes were quickly dashed.

The Algerian Conundrum

Algiers presented a much thornier problem. In 1785, Algiers had captured two American ships. The ships’ crews remained imprisoned in horrific conditions for the next decade while awaiting a ransom or other settlement agreement. American negotiators had to settle on a price for release, but doing so would set a precedent for Algerian expectations in future captures or the cost of future tribute.

…

Paying tribute required separate negotiations with each Barbary State, and the conditions of tribute were not guaranteed in perpetuity. Each state could demand more tribute or resume seizing ships and crews for individual ransoms. Continuing to pay ransoms was untenable because it led to increased insurance rates on U.S. merchant ships entering the Mediterranean. Americans held for ransom also faced abysmal conditions while in captivity.

…

The threat of potential American force did not diminish Algerian demands. Following the news of the United States’ Act to Provide a Naval Armament, Hassan Bashaw, Dey of Algiers, raised his demands for a tribute that included personal payments to himself, replenishment of the Algerian treasury, ransom for captive sailors, and even the construction of an Algerian warship.

A Treaty of Peace and Amity was reached in the fall of 1795 that reduced the tribute payment to about a third of the original demand and ensured safe passage for American merchant ships. Congress was bitterly divided over support for the treaty, but it was ultimately seen as a necessary resolution to the Algerian issue. With the treaty in place, the United States could turn its attention to the two remaining Barbary States, Tunis and Tripoli.

Treaties with both Tunis and Tripoli were signed by the fall of 1797, clearing the way for safe American transit of the Mediterranean. But this safe transit came at a substantial ongoing cost in the form of tribute to Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. The treaties were only as good as the last payment, and the leaders of all three Barbary States were willing to threaten American shipping in order to see payments not only continue but increase over time.

…

The Shores of Tripoli

Preble bombarded Tripoli and attacked its fleet in the harbor several times in an effort to defeat the Tripolitans. While the attacks had some effect, it was the coordinated assault by land that eventually forced Karamanli to surrender. Karamanli had taken power in Tripoli by deposing his brother, Hamet Karamanli, who was exiled to Alexandria, Egypt. U.S. envoys decided to back Hamet Karamanli in an attempt to regain power over Yusef. A small contingent of U.S. Marines, led by former U.S. consul to Tunis William Eaton, joined Hamet Karamanli and a mercenary army to march along the North African coast from Alexandria. Their intent was to take Derna, then Benghazi, and finally Tripoli itself. At the Battle of Derna, Eaton and his forces were assisted by shore bombardment from three American ships under the command of Master Commandant Isaac Hull. Yusef Karamanli, following his defeat at Derna, decided that the combined forces were more than likely to make it to Tripoli. He negotiated a peace agreement that retained his power.

The exploits of Preble and his fleet of young naval officers became enshrined in the heritage of the fledgling United States Navy. Many of the officers, who later became known as “Preble’s Boys,” went on to earn fame in the War of 1812, including Isaac Hull, James Lawrence, Stephen Decatur, Thomas Macdonough, and William Bainbridge.

The Tripolitan victory did not, however, ensure peaceful free passage for U.S. merchants. European nations were still paying tribute to the Barbary States, and Britain still opposed American trade and navigation in the Mediterranean – a stance that would contribute to the War of 1812. In 1815, Algiers, backed by Britain, attempted to attack U.S. ships again in lieu of receiving tribute. A U.S. Navy squadron led by Stephen Decatur arrived in the Mediterranean and, defeating the Algerian fleet, promptly forced a new negotiated peace with Algiers, as well as Tunis and Tripoli.

We know this business model. We know this tradition. We know what it takes to defeat it.

All it takes is will to understand the motivations of those demanding tribute, and your own motivations.

Human behavior 101: You get more of what you reward, less of what you punish. Sort of a high end example of "The art of the deal"...As noted prior, it takes will and a strong Navy and Marine Corps. Don't make empty threats, state the acceptable conditions and the penalty for non-compliance, and punish violations promptly and violently. FAFO in a nutshell.

I would say something here, but Kipling said it better.

https://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poem/poems_danegeld.htm