It is with nations as with people; they will show you what they value by what they spend their money on.

Details always matter in a budget, but with inflationary pressures unseen in decades, a significant land war in Europe, and an accelerated naval challenge by the People’s Republic of China, the actual buying power of a budget and where you spend it matters more than usual.

Few are better positioned to explain the bold faced concerns with the 2024 Defense Budget to navalists than our friend Bryan McGrath, returning again for a guest post that will bring you up to speed.

Over to you Bryan.

Last week, the Biden Administration delivered its 2024 Defense Budget to Capitol Hill, and it contained a mixed bag for the Navy. On one hand, all major Navy accounts were increased over the 2023 budget, and there were notable investments in readiness and weapons procurement. On the other hand, no major account’s increase kept pace with inflation, a problematic fact and the source of most defense hawks’ calls for increasing defense spending above the rate of inflation. In a time of growing great power competition and a massive naval buildup by China, the Navy is at best, treading water.

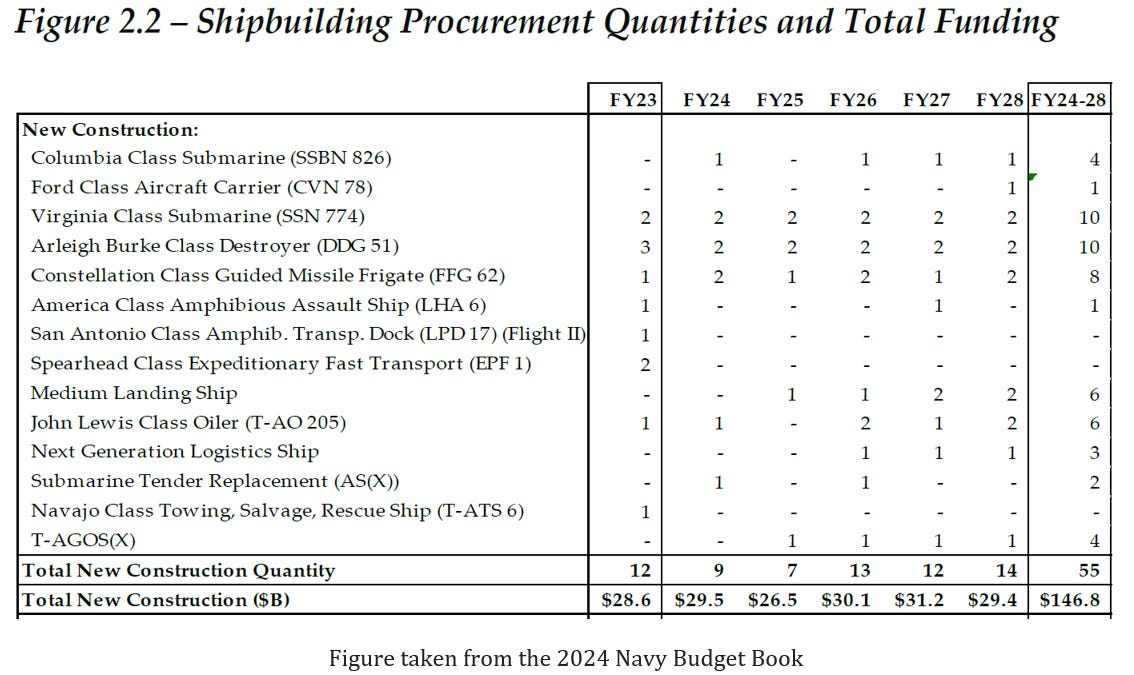

No account within the Navy budget is watched as closely as the shipbuilding account, often referred to by the abbreviation “SCN” for “Shipbuilding and Conversion (Navy).” The 2024 budget provides $29.5B to procure 9 battle force ships (1 ballistic missile submarine, 2 attack submarines, 2 destroyers, 2 frigates, 1 replenishment ship, and 1 submarine tender). The devil is in the details however, as while the $29.5B figure is 3% higher than the 2023 total, 12 ships were procured in the 2023 budget, including 3 destroyers and an LPD 17 Flight II amphibious ship. Additionally, in an age of Chinese naval expansion and a growing emphasis on American Seapower, the projected spend on new construction ships is $100M (constant dollars) less in the fifth and final year (FY28) of this budget than it is in the first (2024). It is difficult to understand how less money in FY28 will buy five more ships than in 2024, when one of the FY28 ships is an aircraft carrier and one is a ballistic missile submarine. Congressional budget hearings are likely to probe this question.

Returning to the LPD 17 Flight II mentioned in the previous paragraph, the 2024 budget submission eliminates future production of this vessel, something that is reported to have caused tension between the Navy and the Marine Corps (see here and here). Apparently, OSD directed at least a “pause” in LPD 17 production while the Navy and Marine Corps conduct amphibious shipping requirement studies. This does not sit well with Marine Corps Commandant General David Berger who recently said that “We cannot decommission a critical element without having a replacement in our hand”. Because the budget also calls for decommissioning three WHIDBEY ISLAND Class LSD’s, force levels will dip below the USMC’s requirement for thirty-one amphibs beginning in 2024. This 31-ship requirement also happens to be a matter of public law. A related issue flowing from a significant drop in the number of amphibious ships is a concomitant drop in demand for the Marine Corps “Ship to Shore Connector” (SSC), a surface effect ship that is being purchased to replace the Navy’s aging “Landing Craft Air Cushion” (LCAC). Five were acquired in 2023, with none in 2024 and two a year thereafter. It is difficult not to see a cause-and-effect relationship between the (then) new Commandant’s 2019 statements about legacy platforms and his willingness to trade force structure for innovation—and the 2024 budget’s realization of these positions.

Navy officials often cite the need to stabilize the shipbuilding profile to provide predictability and certainty to the shipbuilding industrial base, especially its workforce. There is within this budget, increased unpredictability, especially with respect to the ships and craft of the amphibious force. Added to the LPD 17 and SSC uncertainty injected in this budget, the Landing Ship Medium (LSM, formerly the Light Amphibious Warship (LAW)) appears in 2025, suggesting that it is filling the gap left by truncating the LPD 17 Flight II line. As these ships are likely to be a fraction of the size of an LPD 17, they are not a useful substitute, either operationally or within the industrial base.

Additionally, the late budget submission did not include (for the second year in a row) the required 30 year shipbuilding plan, a document that among other things, signals to that shipbuilding industrial base the Navy’s future path. These signals are required to spur the kind of internal investment necessary to increase production capacity above what has been for decades, an industry tuned to meet bare minimums for peacetime production. In a controversial move in the 2023 shipbuilding plan, the Navy laid out three different shipbuilding plans, putting forward a menu of options that it could pursue if resources were made available.

Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro recently indicated that the 2024 plan will continue the practice of multiple alternative futures, saying “If you look at the numbers very carefully, you’ll see that in the first 10 years of that plan, the numbers don’t change. And that is important, because the industry does need a steady signal of what our intentions actually are…take a look at the numbers in those first 10 (year) tables and you’ll see a tremendous amount of stability and flexibility, even compared to last year.” Del Toro appears to suggest that unlike the 2023 plan (in which the second five-year tranche of ships differs), each of the three forthcoming options will put forward the same plan for the first ten years. This would be a helpful start toward providing stability, but it is far less of an impact than year-to-year consistency, which recent plans have lacked. Additionally, while submitting three plans provides a vehicle for surfacing repressed Navy desires, it undercuts the suggestion that the plans are tied in any meaningful way to strategy.

A look back at the FY2011 shipbuilding plan is insightful, if only as a means for displaying the predictive value of 30-year plans. If the Obama Administration’s plan had been followed, there would be 320 battle force ships in the Navy inventory in FY 2024. The Biden budget submitted last week supports only 293 battle force ships. In the meantime, numerous 30-Year Plans have been submitted in which year to year goals and force mixes have changed, sometimes significantly.

A final question that the 2024 budget submission raises is how OSD and the Navy responded to the change to the Navy’s Title 10 mission brought about by the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, a change that OSD was dead-set against. The most obvious sign of lukewarm implementation is the aforementioned truncation of the LPD 17 Flight II, a ship of significant flexibility and capability throughout the continuum of conflict. As the previous Title 10 mission was devoted to operations incident to combat at sea, OSD pressure on the Navy and Marine Corps led to a short-sighted (and strategically dubious) focus on capabilities more valuable AFTER the shooting starts than before, and the LPD 17 was seen as vulnerable. Putting aside the fact that part of that vulnerability resides in the Navy’s failure to make use of available deck space for offensive power, the new mission and its emphasis on peacetime operations that protect and sustain both security and prosperity created an even greater need for these ships.

Finally, not only was the mission of the Navy changed by the 2023 NDAA, but a Congressional Commission on the Future of the Navy was directed. This commission has not yet been named or begin its activities, but it seems clear that as it moves forward, it should take the enhanced Title 10 mission statement as its central framing notion and provide insight into appropriate fleet designs based on the funding levels specified by the enabling legislation.

Bryan McGrath is the Managing Director of The FerryBridge Group LLC. His opinions are his and do not represent those of his clients.

Good summary. It appears that the problem is basically twofold: (1) Getting a secure funding path to put the Navy where it needs to be, and (2) OSD. The first requires de-emphasis of handout social programs to the benefit of defense. The second getting OSD out of the granular part of shipbuilding. I leave it to the reader to figure out the likelihood of either under the current "Administration".

Ships and equipment are important.

Also important is how you use that equipment - see Russia's attack on Kyiv.

Also important is that men use the equipment. How well are they trained and does the training match what is needed when the balloon goes up.

Also what lessons from Ukraine can the Navy apply to the future?

Aircraft carriers are not tanks. Destroyers and Cruisers are not infantry.