I have been trying for awhile to think of another occasion where two nations are in - what officially is framed as - an existential war and the parties allow economic trade to continue between and through the two.

Ukraine is fighting for her right to be an ongoing independent nation, and Russia is fighting to reform her empire in a more favorable way.

Great Britain didn’t allow Germany to export goods through British ports in 1940, and yet …

When the grain deal was brokered last July, António Guterres, the secretary-general of the UN, called it a “beacon of hope” — and rightly so. Reaching an agreement of this kind was a remarkable achievement and a big, if rare, victory for international diplomacy. It contributed to significantly lowering grain prices and avoided a collapse in Ukrainian exports (which only declined by around 30%) — effectively preventing a potential global humanitarian disaster. Over the past year, more than 1,000 ships (containing nearly 33 million metric tons of grain and other foodstuffs) left Ukraine from three Ukrainian ports: Odesa, Chornomorsk and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi.

On July 17, however, Putin pulled out of the deal. Russia’s move didn’t come out of the blue. As Western sanctions increased, the deal had started coming under growing strain, with the Kremlin claiming that the West wasn’t holding up its end of the bargain, which allowed for more Russian agricultural and fertiliser exports. For this to happen, Russia insisted on reconnecting the Russian Agricultural Bank to the Swift international payment system and, among other things, the unblocking of assets and accounts of those Russian companies involved in food and fertiliser exports.

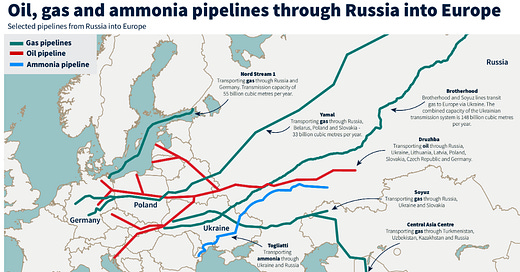

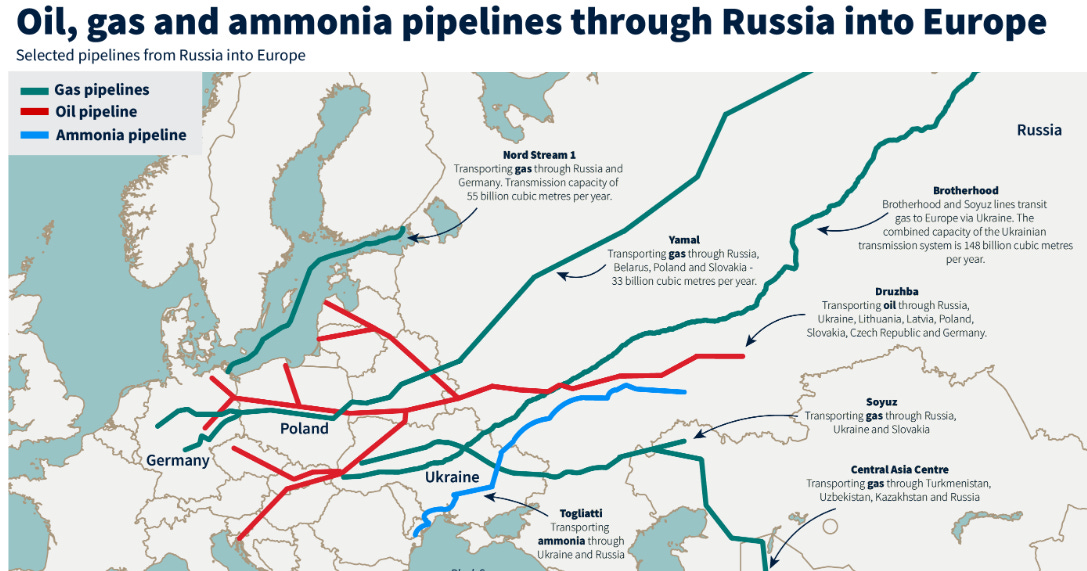

But the most important demand was the resumption of the Togliatti-Odessa ammonia pipeline, which runs from the Russian city of Togliatti to various Black Sea ports in Ukraine, and which prior to the war exported 2.5 million tonnes of ammonia annually. As part of the negotiations over the Black Sea Grain Initiative, Kyiv and Moscow struck a deal to allow the safe passage of ammonia through the pipeline — but the latter was never reopened by Ukraine. Last September, the UN urged Ukraine to resume its transport, in view of ammonia fertiliser’s crucial role in supporting global agricultural productions, but to no avail.

Then, last month, Russia once again demanded once the reopening of the pipeline as a condition for renewing the Black Sea Grain Initiative. Just a few days later, a section of it located in Ukrainian territory was blown up

…

t appears a similar story of obstruction seems to be playing out with Russian gas exports. Despite the war, Russian gas has continued to flow through Ukraine into Europe — softening the blow of the EU’s intention of decoupling from Russian energy while allowing Ukraine to raise much-needed cash in the form of transit fees. In a recent interview with the Financial Times, however, German Galushchenko, Ukraine’s energy minister, said that Kyiv is unlikely to renew the gas transit deal when Ukraine’s supply contract with Gazprom expires in 2024.

In practice, this would mean the closure of one of the last arteries still carrying Russian gas to Europe, a move which would severely weaken many energy-dependent EU countries. Recent analysis by Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy suggests that deliveries to EU countries “could drop to between 10 and 16 billion cubic meters (45 to 73% of current levels)”, according to a June analysis by Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, leaving Europe with a shortfall that cannot currently be replaced with greater liquefied natural gas imports from the US and Qatar.

Yep … Russian pipelines to world markets run through…Ukraine.

There are two explanations here that make sense.

There is significant international pressure to keep the flow of food, fuel, and fertilizer going in order to keep global prices from spiking.

Business interests are looking long term to an end to a war and resumption of trade as before - and don’t want a long time to rebuild infrastructure or relationships.

Perhaps a bit of both.

Will the war continue through 2024? It appears so…but it is going to do what all wars do as they grow in length - they will get more dangerous and carry the significant risk that they will create more friction than can be contained locally.

As also mentioned in the article, Ukrainian grain being dumped on the European markets are creating problems in the European agricultural sector that simply cannot compete with the fire sale prices.

The cost of fertilizer globally doesn’t just make everything more expensive, it will take a fair bit of land out of production, further impacting supply at some point.

More price and supply problems in Europe from natural gas supply issues to top it off?

Winter is coming…and the war is starting to look like the Western Front in 1917.

Yes, I know this is looking like Russo-Ukrainian War week at CDRSalamander, but it’s important.

…and we haven’t even talked about the Russian pipelines through Poland…

"War is a racket." - Major General Smedley D. Butler, USMC

Your two explanations here are, I think, broadly correct: it's about moderating global commodity prices. The Europeans are also broadly neutral because it is in their interest to be neutral. NATO is supposed to be a defensive alliance per the text of the treaty itself. It is not supposed to be an offensive pact that requires all parties to intervene when a third party to the treaty is attacked. But that is not what the US wants NATO to be. There's a gap between what it is, legally, and what the US wants it to be, practically, which is an extension of its own will.

This issue is similar to the issues faced by the Allies during WW2. Triangular trade with Germany thrived throughout WW2 because there were so many "gaps" with neutral countries. The kind of relatively effective blockade of WW1 was not possible because Germany had France by 1940 and much of Eastern Europe by late 1941. That type of geography issue is also a problem today like it was then. The Black Sea was (not coincidentally) a major avenue for imports destined for Germany. Ending that trade was one of the main motivations for the Italian campaign in 1943; it's why Stalin was so fervent in demanding it. The only way to stop neutral countries from trading with an enemy is to end their neutrality by attacking them. The US doesn't want to do that and can't really do that officially apart from looking the other way when mysterious frogmen blow up pipelines.