Follow through. For some things, that is what matters … and the numbers tell the story.

So, here we are over six years, roughly one-and-a-half the time it took for the USA to fight WWII - after the drowning deaths of 17 Sailors in the collisions of the destroyers FITZGERALD and MCCAIN in WESTPAC that, we were told, was going to be a turning point for our Navy to really - and we meant it this time - refocus on the fundamentals that we failed to maintain which were - outside the ultimate responsibilities of command - the latent causes of the collisions; manning, maintenance, and training.

In January of 2019, we discussed The Fort Report (in a post with over 600 comment on the OG CDR Salamander blog),

When Fort walked into the trash-strewn CIC in the wake of the disaster, he was hit with the acrid smell of urine. He saw kettlebells on the floor and bottles filled with pee. Some radar controls didn’t work and he soon discovered crew members who didn’t know how to use them anyway.

...

Since 2015, the Fitz had lacked a quartermaster chief petty officer, ...

...

When Fort arrived at her (LT Natalie Combs) CIC desk, he found a stack of abandoned paperwork: “She was most likely consumed and distracted by a review of Operations Department paperwork for the three and a half hours of her watch prior to the collision,” Fort wrote.

...

“Procedural compliance by Bridge watchstanders is not the norm onboard FTZ, as evidenced by numerous, almost routine, violations of the CO’s standing orders,” not to mention radio transmissions laced with profanity and “unprofessional humor,” Fort found.

...

About three weeks after the ACX Crystal disaster, Fort’s investigators sprang a rules of the road pop quiz on Fitz’s officers.

It didn’t go well. The 22 who took the test averaged a score of 59 percent, Fort wrote.

“Only 3 of 22 Officers achieved a score over 80%,” he added, with seven officers scoring below 50 percent.

The same exam was administered to the wardroom of another unnamed destroyer as a control group, and those officers scored similarly dismal marks.

The XO Babbitt, Coppock and two other officers refused to take the test, according to the report.

As Geoff Ziezulewicz reported back in 2019 as well;

In the 19 months since the fatal collision, the Navy’s Readiness Reform Oversight Council has made “significant progress” in implementing reforms called for in several top-level Navy reviews of the Fitzgerald and McCain collisions — nearly 75 percent of the 111 recommendations slated to be implemented by the end of 2018, Hicks added.

Significant progress? Progress on systemic and latent causes, or just immediate check list items? Are we killing alligators as we see them, or are we draining the swamp?

I’m sorry, I need to see your math.

There was a lot to look at. Hard to quantify leadership and culture, but readiness? Imperfect, but you can quantify that. Personnel? You can fudge some things…but only so much.

Let’s look back at the exceptional article from FEB 2019 from T. Christian Miller, Megan Rose and Robert Faturechi at ProPublica.

Benson also worried about the ship’s physical state. The ship had recently spent eight months in Yokosuka’s repair yards, where workers installed a new defensive system, overhauled its turbine shafts and painted it a new coat of Navy gray. But hundreds of repairs, major and minor, remained to be done.

Then there was the crew. In those eight months, nearly 40 percent of the Fitzgerald’s crew had turned over. The Navy replaced them with younger, less-seasoned sailors and officers, leaving the Fitzgerald with the highest percentage of new crew members of any destroyer in the fleet. But naval commanders had skimped even further, cutting into the number of sailors Benson needed to keep the ship running smoothly.

The Fitzgerald had around 270 people total — short of the 303 sailors called for by the Navy. Key positions were vacant, despite repeated requests from the Fitzgerald to Navy higher-ups. The senior enlisted quartermaster position — charged with training inexperienced sailors to steer the ship — had gone unfilled for more than two years. The technician in charge of the ship’s radar was on medical leave, with no replacement. The personnel shortages made it difficult to post watches on both the starboard and port sides of the ship, a once-common Navy practice.

…

Lt. Cmdr. Ritarsha Furqan, the ship’s combat officer, worried that the constant pace was not providing enough time for necessary training and repairs. “We’d find a part, find a body, make do and get underway,” Furqan later testified in a legal proceeding. “Sometimes it felt like it was unsafe or wrong.”

In March, Furqan confronted Shu: “We are not ready,” she told him. Shu, she testified, told her that he had already delivered that message to superiors. The missions would continue. Benson’s first test of leadership was improving the ship’s state of readiness. In the months at sea after dry dock, the 22-year-old destroyer deteriorated as its regular maintenance was repeatedly pushed back. Benson spent his first week in command as though he were again captain of an aging minesweeper, trying to tackle hundreds of repairs and begging technicians to fly over from the United States for help.

Yep … remember, before the collision, both the ship and Big Navy were bragging that in addition to the undermanned ship’s company doing their work, they were bragging that they were doing depot level work that could/would not be done ashore?

Not fun times, not fun times.

Almost a year ago, Megan Eckstein brought us up to speed;

For the last five years, Bud Couch has been on a quest to make the surface navy safer.

As the director of operational safety at Naval Surface Force Pacific, Couch helped generate 117 recommendations after two U.S. Navy destroyers were involved in separate fatal collisions in summer 2017. But that wasn’t enough.

He knew those recommendations would help, but they wouldn’t fundamentally change how the Navy looked at readiness and safety. So Couch set off to reframe the conversation.

“Given the billions of dollars we’ve dumped into the readiness accounts, and literally the thousands of mishap report recommendations we’ve accomplished, why aren’t we getting measurably better?” he wondered aloud during an interview with Defense News.

That is, after all, the operative question.

In 2018, Naval Surface Force Pacific established the Human Factors Oversight Council and since then has relied on the group to measure a broad range of sailor-related data, from how much sleep each individual sailor gets each night, and therefore how fit one is to stand watch, to how much training a sailor received and how a sailor scored on proficiency tests, which informs ship assignments. The group looks at a ship’s mishaps during maintenance to determine how likely they are — statistically speaking — to have a certain type of mishap during at-sea operations.

If recommendations alone won’t stop fatal collisions, data might, the argument went.

“We ended up coming up with this thing we call the six common traits of a mishap ship,” said Couch, a former Navy helicopter pilot and amphibious ship captain. “The traits themselves are interesting — it’s kind of a cool checklist to walk around as a leader and say: ‘Are these things happening on my ship?’

“But perhaps more important than the traits themselves is using those variables to ground ourselves in this theory of organizational drift into failure, and then using that theory to go back and think about how we would combat that drift at the [fleet] level and at the [ship] level.”

This data-centric focus on how sailor readiness contributes to surface fleet safety comes as the commander of Naval Surface Forces, Vice Adm. Roy Kitchener, works to make the fatal collisions of destroyers Fitzgerald and John S. McCain a course-altering moment for the surface warfare community.

“It was an inflection point for us,” Kitchener said. “We reset our community.”

That, the admiral explained, was done by making changes to organization, training, manning policies and maintenance prioritization — and the Navy isn’t done yet.

“We want to be defined by all the good things sailors are doing every day, not these events that we’re talking about today.”

Here we are, halfway through May of 2023, and we’re still talking about the events.

Thanks to navalist twitter datahound and reader of all congressional thingys Charlie B, … let’s cut to the chase.

From the recent INSURV report.

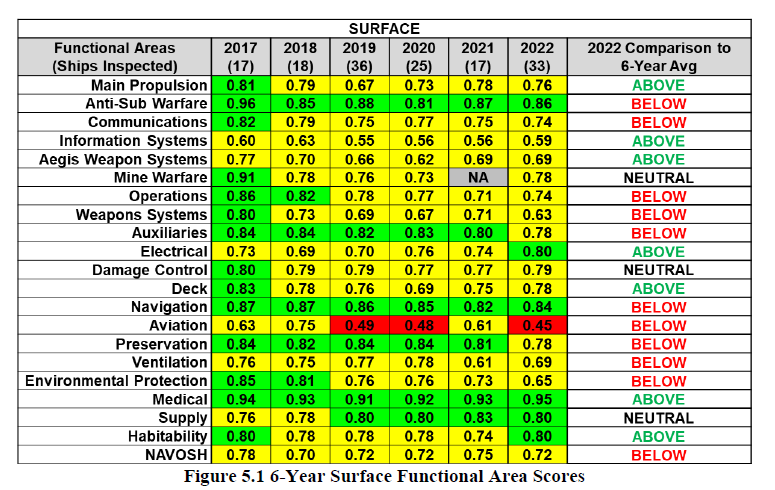

Compared to that horribilis annus of 2017, how have we done?

Besides Electrical, Medical, and Supply - we are worse.

As someone who spent WAY too much time in the readiness/material condition reporting world, there are one of two reasons for this.

In 2017 we just has systemic lying on readiness reports, but since then we’ve stopped that and with the billions of dollars and seabags full of Sailor sweat, we now have more accurate reporting, but it just appears lower compared to the Potemkin readiness reporting in 2017.

We really don’t care. After some nice reports and a few somber faces to the camera and the odd funeral or 17 … as an institution we regressed to the mean, only worse now.

#1 I can accept, but for me to accept this, I need a few things; confession, your math, repentance, accountability. As we have not seen the first and second, only passive hints at the third, and sacrificial bits of the fourth, I’m afraid we have to assume #2 represents 50.1% of the reason.

Why? Why would this be?

Ask yourself; has leadership and Congress been focused on maintenance? Have you seen a surge of shore support? Have we systemically changed our mindset (outside a few specific areas)? What are our incentives and disincentives changing to bring about different results?

I’d really like to see the CASREP data too while we are at it.

Really.

I’d like you to keep this in mind - we are talking about 1.5 WorldWars here to move the needle in the right direction - and it’s going in the wrong direction.

Congress should call each of the service chiefs before them and ask them point blank what the mission of their branch is. And the first one to include the word "diversity" or "inclusion" should be fired. The only acecptable answer is, and I quote Conan the Barbarian, "To crush our enemies. See them driven before you. And to hear the lamentations of their women." Or at least something to that effect.

Why am I not surprised we are heading in the wrong direction, given all the efforts to assimilate transgenders, the focus on using correct pronouns, and all the time wasted on "woke" related crew training and the splendor of Gay Pride Month celebrations.