Besides a little post a bit over a month ago, I haven’t had much to say about President Trump’s nominee to be SECNAV. I’m not sure what there is to say at this point. Once he gets through confirmation and into his tenure, there will be a things to discuss, maybe.

Once in the job, as a business man, I am sure one of the first things he will see up close if he does not already is that our Navy has a branding problem, a cultural problem, and a toxic relationship with our underwriter, Congress.

To kick the week off, let’s go back a couple of weeks to Bradley Peniston and Meghan Myers at Defense One a case that brings together all three:

The Navy never wanted to modernize its Ticonderoga guided-missile cruisers, preferring to spend the money on newer ships and technology. But lawmakers balked at losing hulls and missile tubes, and ordered the service to refit some of its remaining cruisers to serve several more years.

Then the Navy botched it, according to a new report by the Government Accountability Office.

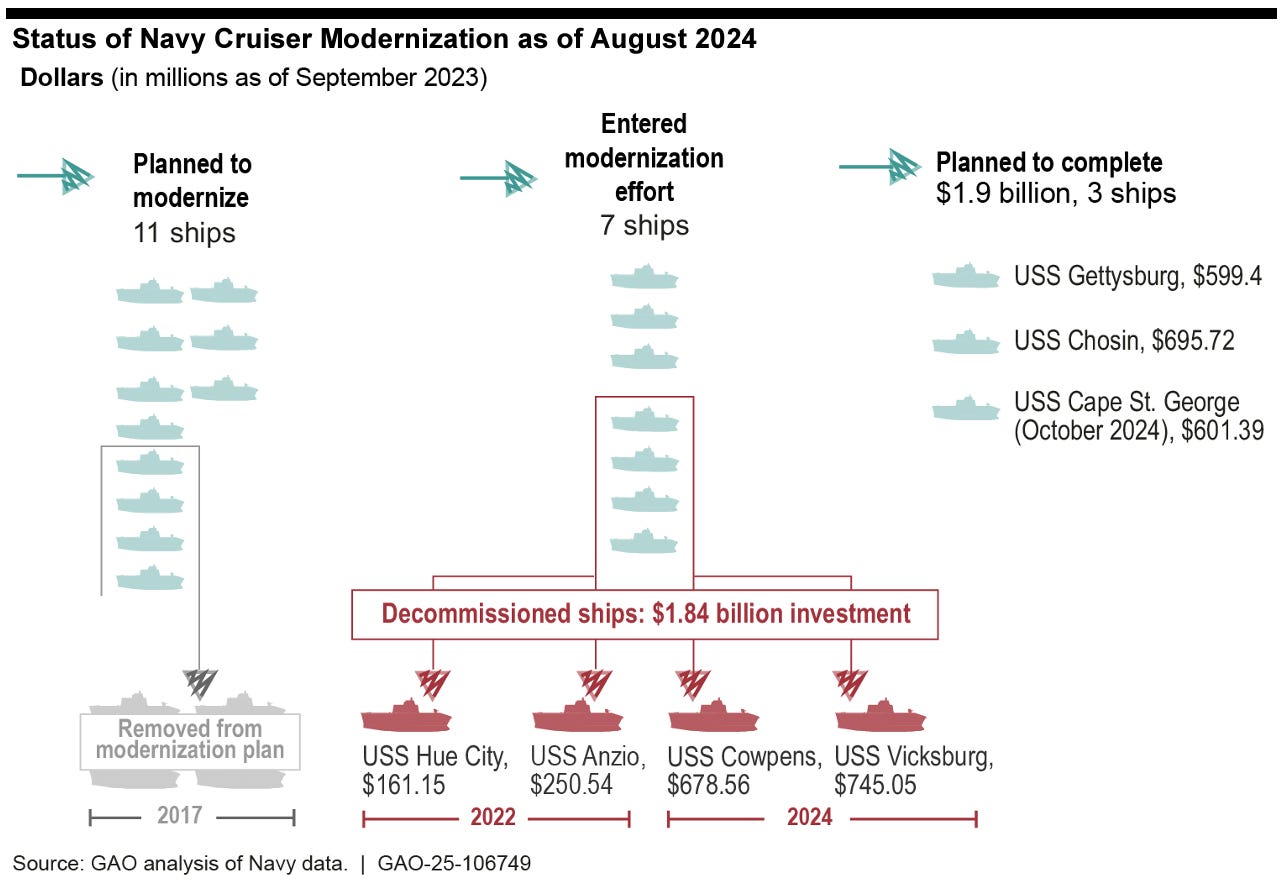

Over a decade, the service spent $3.7 billion on a poorly planned, inconsistently managed effort that, GAO wrote, “wasted $1.84 billion” on four cruisers that never deployed again.

Anyone who has raised children can see exactly what the Navy was doing, institutionally it was throwing a passive-aggressive hissy fit.

“I don’t want to mow the yard, but you’re going to force me? Fine, I’ll mow the yard.”

That is one theory. The other theory, the more distressing one, is that NAVSEA is simply that incompetent. It is focused on something, but its core mission, notsomuch.

Yes, you can say this is equally about a dysfunctional Congress, but that does not matter. At the end of the day, the US Navy relies on Congress for its funding. No organization can expect to have a productive relationship with those who pay their bills if it continues to treat their sponsors with contempt, perpetuate a culture of untruth, and wantonly throw money away.

When addressing an organization with branding, cultural, and relationship issues, you must first examine three areas: process, product, and people.

That is where you will find the source of your problems. You can start finding out the roots of the larger problem by digging around with the Cruiser debacle. That will draw out the low-performance, low-reliability players right away. Anyone who gets overtly defensive, makes excuses, or tries to blame Congress or industry — immediate career adjustment.

The Navy has yet to identify the root causes of unplanned work or develop and codify root cause mitigation strategies to prevent poor planning from similarly affecting future surface ship modernization efforts.

If he can’t get answers to the above from the report that survive the follow-on questions, it is time to bring in experience from the private sector. As I like to say here, root and branch.

If you wonder why the US Navy is now the world’s second largest navy, this might help.

Even though the Navy used more than $2 billion of procurement funding for cruiser modernization, it did not implement planning and oversight tools typical of high dollar major defense acquisition programs following the major capability acquisition pathways because it is not an acquisition program. Further, the Navy also failed to factor key elements into its planning, such as the condition of the ships and stakeholder involvement, including RMC officials and Port Engineers.

Who was responsible for this? Name(s) and N-code(s)?

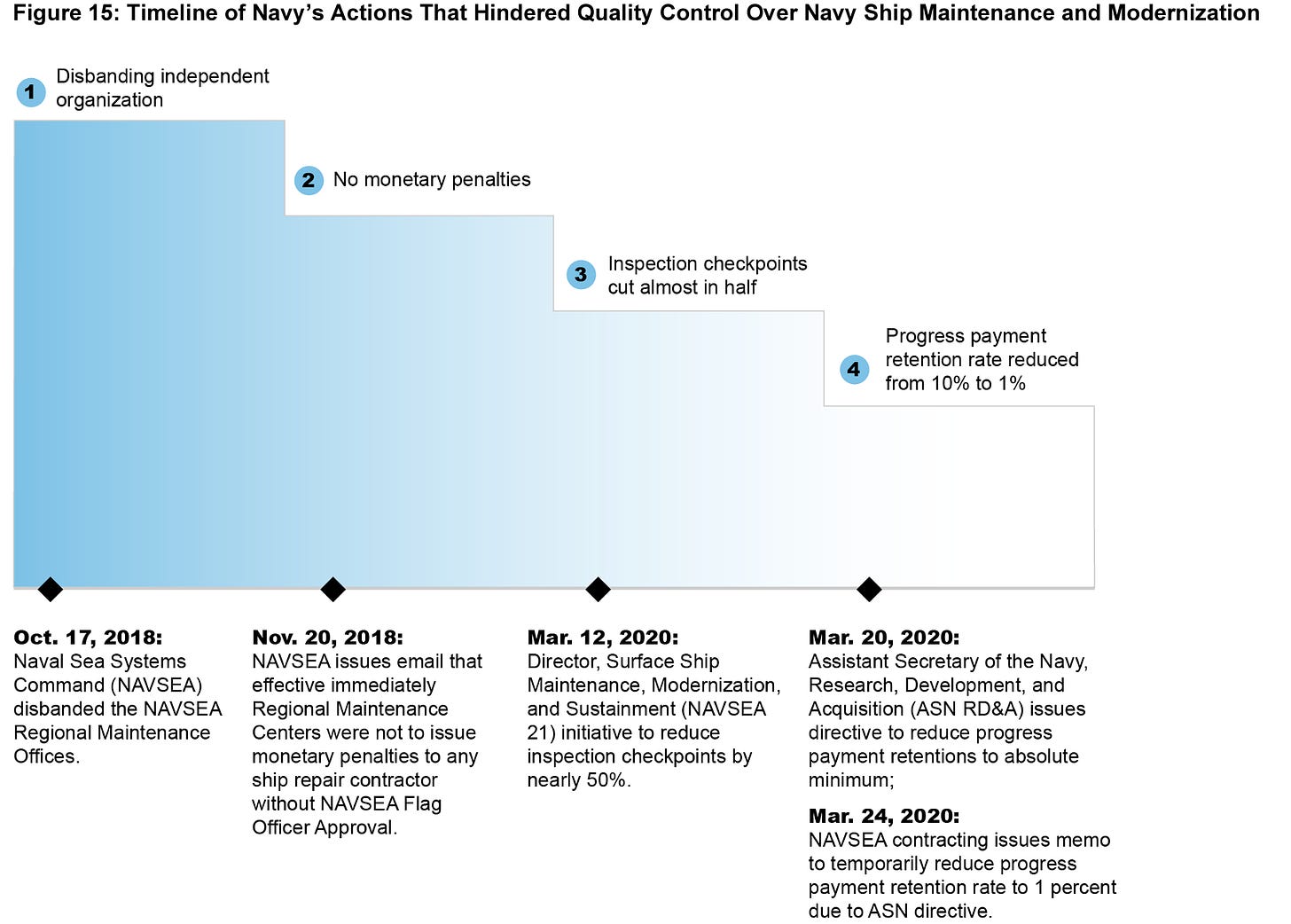

Despite widespread instances of poor-quality work during the cruiser modernization effort, NAVSEA senior leadership discouraged RMCs and contracting officials from fully using key quality assurance tools to maintain the industrial base and a positive working relationship with the ship repair industry.

If quality is not job one, then what is?

What is the first thing to come to mind when reading this? The US automobile industry in the 1970s.

In early March 2020, NAVSEA leadership finalized and implemented an initiative that decreased the number of inspection checkpoints during a ship repair and modernization period by almost 50 percent. Before work can be accepted by the Navy, quality assurance personnel inspect it and determine if it meets contract requirements. Complex work sometimes involves in-process inspections, called checkpoints, to ensure critical work is done in accordance with contract specifications. According to a March 12, 2020, NAVSEA memorandum, the Navy reduced the number of inspection checkpoints during ship repair and modernization periods to improve contractor efficiency and reduce the RMC’s checkpoint burden. Navy senior leadership, in the memorandum, stated that this initiative would aid in ontime delivery.

Regulars here will recall with discussing our acquisition and program management system being “accretion-encumbered” by the addition of layers of mutually disruptive bureaucratic requirements that no one is really sure how they got here nor how to make them work with each other. NAVSEA seems to have the same problem.

The Navy experienced challenges overseeing its maintenance and modernization efforts for cruisers and other surface ships, in part, because key stakeholders do not have clear roles for coordinating complex work packages during maintenance and modernization periods. For example, while key Navy fleet guidance identified RMCs as responsible for all oversight, RMCs do not have the ability to ensure that all stakeholders act in coordination with the larger CNO maintenance period effort. Further, in a 2024 report about Navy modernization on surface ships, NAVSEA also found that this fleet guidance conflicts with other guidance, leading to uncoordinated work among key stakeholders. As a result, the Navy has experienced late and incomplete schedules, gaps in oversight, and inefficient working arrangements during these CNO periods across cruiser modernization and other surface ship modernization efforts.

BZ to CBO for putting into pictures something that is difficult to grasp the full clown car experience.

How do you write that into a FITREP bullet? IDK.

Why should this recent experience be on the future SECNAV’s short?

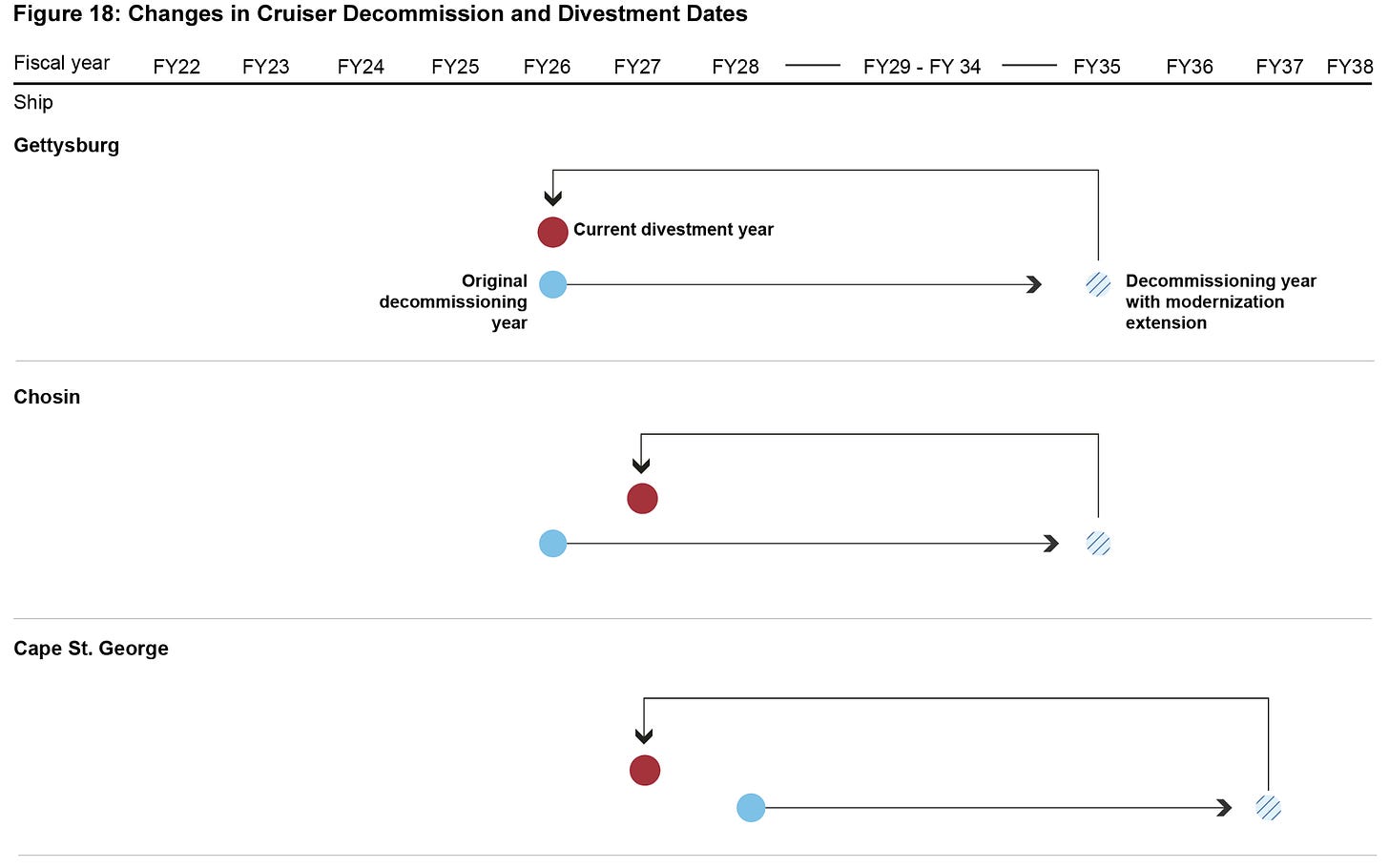

Effectively modernizing ships is critical since the United States cannot build enough ships to increase the size of the fleet while also divesting ships before the end of their service lives.

If war is to come west of the international date line, it will predominately be a maritime and aerospace fight. We no longer have the luxury of time.

At the end of the report, there is a series of recommendations for the SECNAV. I would recommend he get a briefing first from the authors of the CBO study, then let OPNAV and NAVSEA people tell their story.

Fixing the people problem is fast, faster if we had civil service reform. Process takes longer. Culture even longer. Change has to start sometime, by someone. The best time is now. The person fate has chosen to be that change agent will be the next SECNAV.

The “rest of the story” is the lingering impact on the crews assigned to the CG MOD ships over the years. They bore the brunt of underfunded maintenance, poor oversight, all while tied to many of the watch requirements of a “commissioned” warship for extended periods, including standing duty etc. An entire generation of officers and enlisted was handed a real mess to live with - and clean up.

This has discouraging echos of Boeing .