Resupply through thousands of miles of hostile waters to your forces well inside the enemy's aircraft reach and a day's sail or two from their home bases.

Your navy intends to bring and keep the fight in to the enemy's backyard, stay there, and defeat them at sea in order to give your nation dominance in their enemy's backyard.

One force has well over a century of dominance in all the world's oceans. A superb tradition of training and combat excellence in these exact waters. It has fewer, but larger ships ... but as well trained as their crews are, they are also under the stress of constant threat and being far away from home waters.

The other force also has a tradition at sea, but at a more distant time. They have good equipment, but in the intangibles, may or may not be a match. Their ships, at least for this engagement, are more numerous, but smaller. Still deadly and with more than the ability to engage the other force - and they are in their backyard.

Am I setting a framework for the Western Pacific and the USN v. the PLAN?

No, not at all. As part of the long-running series of battles to keep Malta supplied, today's FbF is about a lesser known batter between Britain's Royal Navy and the Regia Marina Italiana at the Battle of Cape Passero off the southeast tip of Sicily in 1940. There are a lot of things to ponder here that do have lessons for what we may face west of Wake.

Via Vince O'Hara;

On October 8 the full weight of the Mediterranean fleet, four battleships, two carriers, a heavy cruiser, five light cruisers and sixteen destroyers, departed Alexandria to provide distant cover for a Malta bound convoy of four steamers. Hidden in part by heavy weather, the convoy made port on October 11 undetected by the Italians. That same day, however, an Italian civil aircraft flying to Libya reported elements of the Mediterranean fleet about 100 miles southeast of the island where they were loitering, waiting to escort three empty cargo vessels back to Alexandria that night. Supermarina had reservations about this sighting because no military aircraft confirmed it; nonetheless, they dispatched several groups of light units to patrol potential transit areas.

They ordered the largest group, 11th Destroyer Flotilla Artigliere, Aviere, Geniere and Camicia Nera, under Captain Carlo Margottini, supported by the 1st Torpedo Boat Flotilla Airone, Alcione and Ariel, under Commander Alberto Banfito to guard the waters east of Malta. Admiral Cunningham, sailing aboard his flag Warspite, established a scouting line of cruisers extending north from his force. The wing ship, light cruiser Ajax, Captain E. D. B. McCarthy, was zig-zagging at 17 knots about seventy miles north of the convoy and about the same distance east, northeast of Malta.

The weather was moderating from earlier thunderstorms. The moon was up and very bright, just four days short of full. The 1st Torpedo Boat Flotilla was proceeding at 17 knots in a long line of bearing with each ship about 5,000 meters or 5,400 yards apart. Alcione saw Ajax first at 0135 hours on October 12 from about 18,000 meters (19,600 yards). Undetected by the cruiser Alcione reported her contact, requested assistance and proceeded directly to the attack. At 0142 Airone, followed shortly thereafter by Ariel, sighted the cruiser and followed their flotilla mate in. Alcione approached Ajax undetected and fired two torpedoes at Ajax's port side from a range of just 1,750 meters (1,900 yards). She then turned away to attack from another direction.

Her half salvo missed its target. At 0155 Ajax finally spotted two strange vessels silhouetted against the bright moonlight, one on either side of her bow just several thousand yards off. These vessels were Airone and Ariel. One minute later Airone fired two torpedoes from a range of only 2,000 yards. Ariel followed at 0157 with two more. Ajax flashed a challenge, and, receiving an inappropriate reply, increased speed and altered course. The four torpedoes all ran wide, although at this point Ajax was still uncertain whether or not she was under attack.

Airone, closing rapidly, fired off another pair of torpedoes from 750 yards (also wide) and resolved Ajax's confusion by opening fire. She snapped off four quick salvos hitting Ajax twice on her bridgeworks and once six feet above her waterline, igniting a fire in a storeroom. The range was down to slightly more than 300 yards when Ajax finally returned fire. Her 112 pound shells smashed the Italian torpedo boat and left her dead in the water. The two antagonists were so close, Ajax's machine guns could sweep Airone's deck. Ajax reduced speed to 25 knots and shifted heading constantly to avoid torpedoes and gunfire. She fired two torpedoes of her own, one of which might have hit, adding to the misery of Airone's crew.

With Airone in a sinking condition, Ajax turned the attention of her main batteries to Ariel, returning her fire and quickly scoring one hit from 4,000 yards. This may have penetrated a magazine because Ariel blew up and sank within a few minutes, taking most of her crew with her. The time was 0214. When Alcione finally returned from her extended maneuver she found the British ship gone, Ariel sunk and Airone on fire and slowly following. She could do nothing but rescue survivors, saving 125, about half the complement of the two ships. Airone finally went under at 0235.

Meanwhile, the 11th Destroyer Flotilla, alerted by Alcione's original message of forty-five prior was hurrying to the battle in an extended column with Artigliere leading followed by Aviere, Camicia Nera and Geniere. Aviere found the British light cruiser first, but Ajax was fully alert and, at 0218, she hit Aviere lightly on her bow before the Italian could fire any torpedoes. Aviere turned and lost contact. Artigliere, the flotilla flagship, came in next. Maneuvering at high speed she fired a single torpedo at Ajax's starboard side, which missed, and began trading gunfire with the cruiser. Initially the Italian, steaming at a high speed and zig-zagging got the better of the exchange, hitting Ajax four times, putting out her radar and knocking out one of her 4" secondary battery.

The moon had just set; reducing the general illumination and depriving Ajax of the backlight that made the Italian ships, stand out. Not equipped with flashless gunpowder, the repeated flashes from Ajax's guns blinded her crew with every salvo. Nonetheless, at 0230 Ajax's gunners finally hit the elusive Artigliere and hit her hard, killing the flotilla commander, Captain Margottini and bringing her to a halt. By 0232 Artigliere was dead in the water and her guns silent. The other two destroyers of the flotilla remained in the offing. Camicia Nera and Ajax exchanged ineffective salvos from about 5,500 yards. Ajax believed she was facing two cruisers, so when Nera disappeared into a smoke screen of her own devise, Ajax used the opportunity to break contact and turn toward the fleet. Geniere, following at some distance, never entered action.

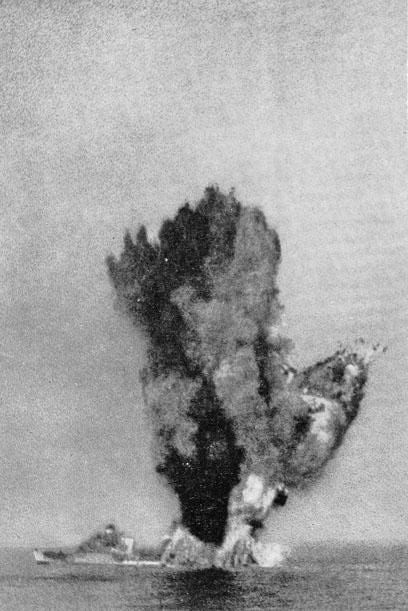

The remainder of Ajax's squadron concentrated on Ajax's position, but arrived to late to see any action. Ajax suffered 13 killed and 22 wounded in this action. She expended 490 6" shells and 4 torpedoes. Ajax's damage was patched up in a couple of weeks and she was back in action by November 5. Camicia Nere took Artigliere in tow, but she was forced to abandon the damaged ship the next morning when two British cruisers and four destroyers approached. The British heavy cruiser York finished off Artigliere at 0905 with torpedoes. Italian reinforcements of three heavy cruisers and three destroyers sailing from Messina arrived too late to save Artigliere or to engage the York group.

O'Hara's analysis is superb and I encourage you to read it in full, but this part is the core;

The Italian destroyers and torpedo boats were supposed to be highly trained, almost elite units. In their attack on the Ajax they enjoyed every possible advantage. They achieved surprise and aggressively pressed their attacks to close range, but accomplished nothing with their principle weapon, the torpedo. The analysis of Marc' Bragadin rings true of the conclusions Supermarina must have drawn at the time and is worth quoting at length: "The reports about the battle gave reason for much reflection. The enemy had escaped with only a few hits scored by the guns of the Airone and the Ariel, damage about equal in all to that suffered by the Aviere alone. The Italians, on the other had, had lost a destroyer and two destroyer escorts; yet the Italian ships were among the more efficient in the Navy, and their commanders were outstanding

...

Each side drew the opposite conclusion. For the Italians night actions were to be avoided. For the British night actions were to be courted. In a way, both Supermarina and the Admiralty used the results of this action to endorse and confirm prewar decisions they had made regarding nighttime operations. Although the Italian Navy conducted night practices during the twenties, in the next decade "a decision was made for the battle fleet to decline night engagements." (7) And guns of 8" and above were not supplied with flashless powder. The Royal Navies, on the other hand trained to fight at night and their doctrine endorsed seeking out and engaging the enemy at night (although, they did not supply even their light forces with flashless powder). These were the lessons drawn from the Action of October 12. But were they the right lessons?

Expectations in the face of reality. Perceived capability compared to relative capability. Well, that and a bit of technology and that critical force multiplier; luck.

You can't wargame morale very well. It is also hard to wargame professional and tactical excellence in the face of an enemy with agency.

The difference in the end is 13 Sailors who won't come home vs 325; one damaged ship on one side, three sunk one damaged on the other.

The primary lesson, you cannot always choose the time and place you will fight. Contrast the Italian experience against that of the Japanese who also faced an enemy with radar while they had none.

The Italians also seem to have been hesitant to use large numbers of torpedoes. Their Destroyers tended to have only a small number of torpedo tubes. Their smaller escorts did not have enough tubes to launch an effective spread.

"In retrospect, the results of this action, at least from the Italian point of view, indicated the need for more training and a re-thinking of their doctrine. Gallantry was not the primary quality required by the situation. Control and coordination would have served the Italians far better."

How true that is: there was no shortage of gallantry among USN forces in the night actions in the Solomons in 1942, but it arguably took the insights and efforts of Burke and Moosbrugger to harness the full potential of American destroyers in night surface actions.

On a tangentially related note, O'Hara's Struggle for the Middle Sea is a masterpiece, and his On Seas Contested is also a highly valuable reference work. I own copies of both and recommend them heartily.