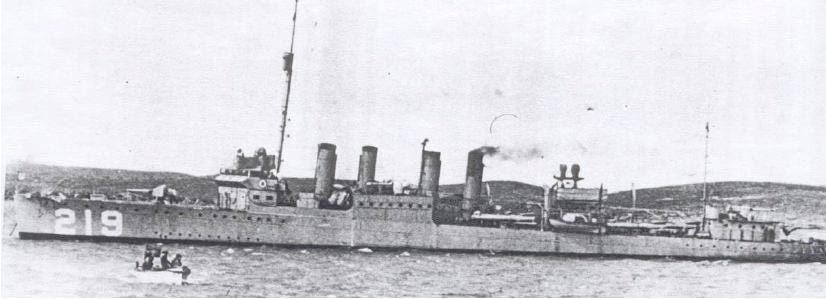

Take a look at these men and then their old, humble 4-stack. DD-219, the USS Edsall.

Since I first posted this back in 2008 the NHHC page has improved on the Edsall. There is a lot to review, but for now - lets just look how she went out, in the end Commanded by Lieutenant (or LCDR depending on the source) J.J. Nix of Memphis TN, in one of the most under-told stories of heroism in US Navy history.

From the USS HOUSTON (CA-30) site,

Three days earlier, on February 25, Admiral Nagumo’s Carrier Strike Force (carriers Soryu and Akagi) sortied from Staring Bay at Kendari, Celebes, and entered the Indian Ocean with the mission “to cut off any escape of the Allied Forces.”

Nagumo’s Support Force consisted of the Third Battleship Division (battleship Hiei and Kirishima) and the Eighth Cruiser Division (heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma). As fate would have it, destroyer Edsall had the misfortune to meet this formidable force on the afternoon of March 1, 1942.

At a position about 250 miles south southeast of Christmas Island the cruiser Tone was the first to spot Edsall at a distance of 15 miles to the northwest. Twelve minutes later Chikuma sighted Edsall too, turned, and opened fire with her 8-inch guns at 1730. The range was extremely long at 21,000 meters (11 nautical miles) and all shots missed. Immediately, Edsall’s skipper, Lieutenant Joshua Nix of Memphis, Tennessee, laid down a smokescreen and began a series of evasive maneuvers that were to frustrate the Japanese for the next hour and a half.

At 1747 battleships Hiei and Kirishima opened fire with their main batteries of 14-inch guns and ordered all units to attack the American destroyer. They began firing at a range of 27,000 meters (14-1/2 nautical miles) and their shots also missed the target. At 1756 Lieutenant Nix courageously turned his ship directly toward Chikuma and closed the range so as to fire his 4- inch guns, but his shots fell short.

Chikuma stopped firing at 1800 when she entered a rain squall and Edsall laid down smoke. However, the intensive fire from all four Japanese ships resumed when the hapless American ship became visible again. Because they were shooting at such long ranges, Lieutenant Nix was able to observe the flash of the guns and turn his ship in time to avoid being hit. He did so approximately every minute. He also abruptly varied his speed from 30 knots to full stop and back again, while making turns as wide as 360- degrees. Since Edsall had suffered damage earlier off Java when one of her depth charges exploded too close astern, her performance had been reduced and there was no hope for her to outrun the enemy and try to escape. She could only stay on station and avoid destruction as long as possible.

Japanese naval gunnery was relatively poor during the early stages of the war, often wasteful and ineffective. The attack on Edsall was a prime example. The official history of Japan’s navy states that some 1,400 rounds were fired in the engagement but, until near the end of the battle, only one round found its mark. However, the action reports of Tone and Chikuma show that two direct hits (meichu) were made on Edsall, one by Hiei at 1824 and another by Tone at 1835. Still, this is an extremely bad percentage and much of it is to the credit of Lieutenant Nix’s superb ship handling under the worst possible circumstances.

So frustrated were the Japanese commanders after an hour had passed that an order went out to the nearby Carrier Strike Force for the assistance of aircraft. Nine dive-bombers from Soryu and eight from Akagi attacked Edsall from 1827 to 1850, even while she made smoke for the fourth time. The planes scored a number of hits with eight 550-pound bombs and nine 1100-pound bombs, setting Edsall on fire in what he Japanese called a raging conflagration (kasai). Whether because the destroyer was now out of control or Lieutenant Nix made a final courageous gesture of defiance, Edsall now turned directly toward her pursers and came dead in the water.

The battleships and cruisers pounded her relentlessly with their secondary batteries until she went down at 1900 in position 13-45S 106-45E, 430 miles south of Java. Cruiser Chikuma picked up an undetermined number of survivors, possibly as many as five.

Under interrogation they revealed the name of their ship, which appears in Chikuma’s log as “Edosooru.”

The Edsall survivors were taken to a POW camp on Celebes and nothing further was ever heard from them. After the war, the Army Graves Registration Service identified the remains of five sailors from the ship: F1 Sidney Amory, MM1 Horace Andrus, MM2 J.R. Cameron, MM3 Larry Vandiver, and F1 Donald Watters.

Lieutenant Nix and his crew never received any official recognition for their heroic stand, which was in the finest tradition of the United States Navy.

Captain Nix; you and your Sailors were Fullbore to the core. BZ.

A side note. Nix was USNA class of 1928. Some of you may have served with his father, Captain Walter Collier Nix, USN (Ret). USNA 54' who passed away in 1998. He wrote the preface to the book on the loss of his father’s ship, A Blue Sea of Blood: Deciphering the Mysterious Fate of the USS Edsall.

It was great to see the update on USS Edsall this week. https://taskandpurpose.com/history/uss-edsall-found-ww2/

Fairly certain I first read about her in "The Fleet the Gods Forgot", but it's been a few years and I need to pick up that book again.

CDR Sal, this is a tough one to process. Essentially, if not for the Japanese records, we'd have little or no information regarding this example of bravery in the face of, well, hopeless odds. Not sunk with all hands, BUT, the survivors, as was all too often the case, perished as Japanese prisoners of war. So, no survivors. Genuinely appreciate you telling the tale of their last stand, so all of us who never knew about USS Edsall will remember their devotion to duty and the nation. May they all rest in peace.