At least for me, a promise you make to a Shipmate, and especially to a dead or dying Shipmate is sacred. A promise needs to be kept not just because it is the honorable thing to do, but it establishes and maintains a culture where a man’s word is his bond, an institution’s word is its bond - promises make are promises kept. With that culture, you can get a lot done. People will do a lot if they know your promises are good. When promises are not kept, well, that is the foundation for cynicism, distrust, and institutional decay.

I’d like to reach back and mostly re-posts a post of mine from 2007 that I stumbled on this AM that bothers me more today than it did then - mostly because we still have not done the right thing.

Think of all the money DOD and the Navy have thrown at wasteful and dishonorable things since 2007. Think of the huge cultural problems we have thrown in to public view from Fat Leonard to having the CNO promote the cancerous Kendi poison on our Navy. That does not happen in isolation.

So, what if I told you for almost eight decades our Navy has refused to dig through the cushions on the couch to get enough change to keep a promise made.

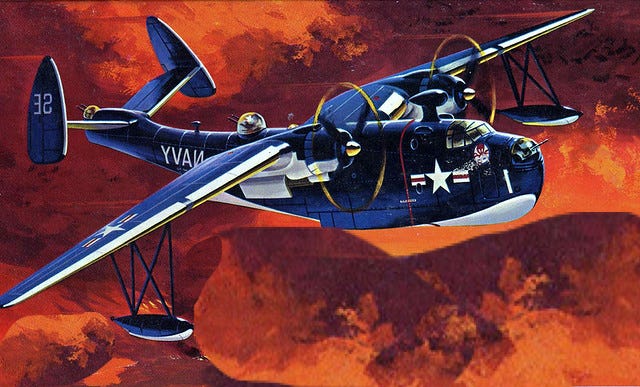

From a forgotten part of the immediate Post-WWII era, I want to introduce you to three crewmen from "George One," a PBM-5 Mariner: Ensign Maxwell A. Lopez, Newport, RI; Frederick Warren Williams, Aviation Machinist’s Mate First Class, Huntington, TN and Wendell K. Hendersin, Aviation Radioman First Class, Sparta, WI. Here is part of their story.

By the time crew members were readying George One for the second flight, the waves were thrashing, yanking the airplane against the lines that tethered it to the assisting boats and roughly jostling the guys inside. Robbins and Caldwell managed to attach four jet-assisted takeoff bottles to the seaplane, but the mooring lines were literally shredding the craft’s aluminum skin. LeBlanc, another World War II veteran with thousands of hours in PBMs, was unperturbed by the conditions. The Pine Island laid a fuel slick to calm the waters and George One cast off and started its run. After what seemed like five miles, the longest run Robbins had ever experienced, LeBlanc fired the JATO bottles and George

One took wing—into a blinding snowstorm.

Robbins says he wasn’t worried, though. He had once received a commendation for a nine-hour flight through fog and clouds in Greenland, and he felt confident in his skills as a radar operator. As Captain Caldwell strapped into the seat in the forward gun turret—now just an observer’s seat—Robbins checked his radarscope. Icebergs below registered strong returns.

As they approached the coast, Robbins reported to the flight deck: “Mountain range 20 miles ahead and scattered icebergs.” The radar return was clear and strong; the terrain matched the charts. But the weather ahead wasn’t clearing. LeBlanc and copilot William Kearns decided to abort the flight and began a long, slow 180-degree turn.

Robbins, standing between the pilots on the airplane’s flight deck, felt a slight bump. He heard LeBlanc and Kearns pour on full power.

And then, nothing. He felt like he was floating. He felt a shaking. His shoulder. He looked up; he was kneeling in snow 20 yards from the cockpit, and the flight engineer, Bill Warr, was standing over him. “We’re all screwed up, Robbie,” Warr said. “I think we’re the only ones alive.”

We know where those Shipmates are buried too.

While the 6 survivors of the crash were able to make it to the coast for pick up by a sea plane, those three men killed in the crash were left behind, their bodies buried in what was meant to be a temporary grave were buried beneath a specific and well-marked area under the starboard leading-edge of the large PBM-5 wing by their fellow crewmen. Weather precluded the Navy from recovering their bodies at the tail end of Operation Highjump. Its always been the wish of these fellow crewmen, the Navy rescuers and the families to have their loved ones returned to US soil.

...

In current times, the Navy, wanting to recover the remains of these heroic men, teamed National Science Foundation/Polar Operations (NSF), the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the Central Identification Lab, Hawaii (CILHI), the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), the National Air and Space Administration (NASA,) the U.S. Navy Casualty Office and other agencies to convene several high-level meetings to determine the logistics and feasibility of the George One crew recovery. The USGS, in conjunction with NASA, commissioned a Chilean P-3 Orion Sub Hunter at a cost of $68,000 to ‘ping’ the site with a highly specialized aerial-borne Ground Penetration Radar (GPR) to pinpoint the George One location and approximate depth of the debris field. The Chilean P-3 located the debris fields approximately 30 to 50 meters below the surface and pinpointed its position to within a .5 by .5 kilometer box.

In 2005 the US Navy halted any further recovery actions lacking known sufficient technology to safely melt down to and recover the remains of the three crewmen.

Well, remember the P-38 we recovered from Greenland in the ‘00s? The same team was ready to go in 2007, but...

Before I even finished the Air & Space articles I had one of those "Aha!" moments. "We've done that! We've done that 5 times! What are they talking about?" I thought.

In 1989, 1990 and 1992 I was lucky enough to be chosen as the photographer of record for the Greenland Expedition Society (GES). After years of research and development, the principals of GES created multiple 268-foot deep shafts and a large cavern at twice the depth of the George One debris field. Our team then maintained that cavern for over 2 months while we disassembled and brought from that cavern to the surface, a WWII P-38 Lightning fighter aircraft. Now known as ‘Glacier Girl’ that airplane flies with 80% original parts.

It's amazing that all that glacier penetration equipment was developed and never had another use - until now!

As a member of the Greenland Expedition Society I immediately stepped forward to offer the experience and equipment used to recover Glacier Girl to US Navy so that they could bring closure for the wonderful families and great people like Robbie Robbins, George Fabik, Gary Pierson, Garey Jones, the Lopez, Hendersin and Williams families and so many others that have kept this mission alive through sheer love and determination. I've reunited members of the ol' Greenland Expedition Society gang and have the glacier penetrating equipment ready to be built in an effort to get the Navy to reconsider a mission to recover these men for their family and for their nation. The Greenland crew is on board, the equipment ready to be built, the Ground Penetrating Radar crew including 3 geophysicists are all on board. JPAC, NSF Polar Operations, USGS, the US Navy Casualty Office are all very cooperative and even seem to be rooting for us. We're all but ready to go.

What is stopping anything from being done?

The last remaining part of the equation is to get the Navy back on board to approve and fund the recovery. A full proposal with options and budgets has already been forwarded to the powers that be @ the Pentagon.

And there it died.

I tried to reach Lou Sapienza, but the email we used to communicate with each other in 2007 is no longer active. He was still trying in 2013, and had Sen. McCain (R-AZ) support and some in the House, but that was not enough.

The Fallen American Veterans Foundation still has the project on its website - but other than than, it seems to have withered on the vine.

Our Shipmates have been waiting for us for a long time in a lonely place. Let's take them home. It is the right thing to do.

two comments:

- it should noted that the survivors had 13 days on the ice

- "The Pine Island laid a fuel slick to calm the waters" what a different time

A promise broken. And they wonder why people won’t enlist? We are seeing a disturbing pattern.